When like Queen Esther, we lose ourselves in beauty or in purpose, it is divine Malkhut asserting itself. And in that state, there is much we can do.

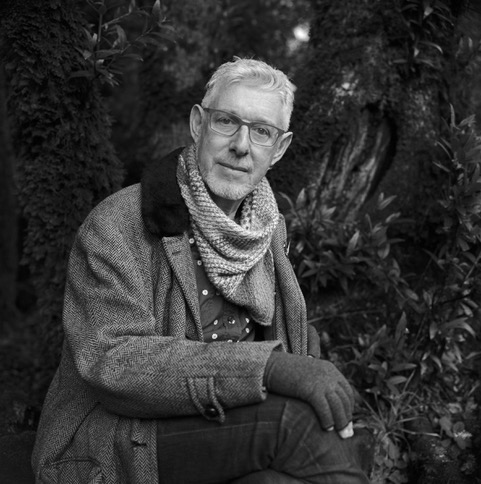

As one of the few rabbis serving a Reconstructionist congregation who can also boast a two-decade career as a professional drag queen, Evolve thought I might have something to say about Purim. Perhaps about the topsy-turviness of it, or the costumery or the prevalence of disguise in both the story and our celebration of it. This is, after all, a holiday of so much concealing and revealing.

And indeed, like most drag queen rabbis I know, I am not at a particular loss for words.

The Book of Esther is indeed filled with disguise and disclosure. Most famous here is Esther, our Jewish hero who wears a disguise that does not involve a mask but rather an omission. She does not reveal her ethnic affiliation (the text says she is commanded this by her cousin Mordecai, but I suspect Esther clearly sees the strategy and purpose here, and the Hebrew text just happens to catch Mordecai mansplaining it). So Esther remains a closeted Jew as she rises to the position of queen of Persia.

But here’s the thing about disguise: while it conceals it also reveals.

At least this is my professional opinion, having spent 21 years on stage as Winnie of the Kinsey Sicks, America’s Favorite Dragapella Beautyshop Quartet. Winnie was a character I played. She was somewhat unlike me—she was proper, she was stern, she was a lesbian. That said, there was a part of me that got expressed through Winnie that had no other place to reveal itself. There were things I could say, freedoms I could embody, that were much harder in pants. In my thousands of hours as Winnie, I was able to live outside of my assigned gender. No one believed me to be a woman, and that wasn’t the point. But I did not have to live up to anyone’s standard of masculinity either. I was free of the corset-tight gender binary, free to be myself—graceful and awkward, confident and anxious, erudite and bumbling, fully at home in my skin, or in hers.

We typically talk about Esther’s disguise as a kind of lessening. She wasn’t her full self because she couldn’t express herself as a Jew. But what might Esther have actually been revealing while she was living in this supposed disguise? The story gives us a sense of it; it is not disguised. All we have to do is look. Esther comes to embody her authority as queen. She holds and uses power. She is not pretending to be the queen of Persia. She is the queen of Persia. When she determines her plan for rescuing the Jews, she doesn’t need Mordecai or anyone else to devise or execute it. She has learned statecraft. And when she commands the Jews to fast with her for three days, it is not clearly a desperate petition to win God’s favor. Her task is one to which she is more than equal. And her prayer and fasting are to make sure that she approaches her task with true humility.

This side of Esther—the part that holds and manages power confidently and humbly—is a part of Esther that probably never would have been expressed had she not come into the palace in her non-Jewish disguise. The Esther who would have lived out her life in the Jewish Quarter of Shushan might never have had the opportunity to know how powerful she was.

There is one key spot in the book of Esther where the text hints at Esther’s true power, and it is one of the two fashion-related moments.

Yes, there are only two fashion-related moments in the book of Esther. Does that surprise you? Especially considering how much of a thing holiday masqueraders and Purim shpielers make of Esther’s beauty and glamour. Forests of crinoline trees have been denuded; flocks of feather boas decimated in the name of Queen Esther costumes!

But in the story, we only touch on Esther’s wardrobe twice. Once is when she becomes engaged. Ahashverosh sets on her head a royal diadem, in Hebrew a “keter malkhut.” (Esther 2:17) The second time is later, leading into the story’s climax, when she goes unbidden to see the king and launch her campaign to save the Jews. In her preparation, the text tells us “vatilbash Ester malkhut”—Esther wears malkhut. (Esther 5:1)

“Malkhut” is the common Hebrew word for “kingdom,” both in the physical, geographic sense, and also in the more abstract meaning of “kingship” or “royalty.” In the book of Esther, the word malkhut is mostly used to refer to Ahashverosh’s realm or his sovereignty.

But what does it mean to say Esther wore “malkhut”? It is an odd formulation. Translations of the book of Esther say that she wore royal garments. But the text doesn’t actually say “garments,” and it could have. Instead, in the simple language of the text, it was malkhut itself that she was wearing.

In Talmud, Rabbi Hanina interprets malkhut here to mean “Ru’akh Hakodesh”—the Holy Divine Spirit (BT Megillah 15a). While Esther’s tribal affiliation remains hidden, there is something of the Divine that is revealing itself through her. When she enters the king’s chamber, it is a gross trivialization to say she is beautiful. Instead, in Rabbi Hanina’s view, she is—literally—a revelation.

Our mystical literature loves this moment because of the array of meanings and associations the concept of Malkhut has in Kabbalah. To capture this, you might need a slight refresher on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life (no offense if you don’t).

In our mystical understanding, the Source of all things is an undifferentiated infinite Oneness. An undifferentiated Divine. “The Tree of Life” is a model that posits a ten-point process through which Divinity differentiates, refines and re-shapes itself in order to form and be present in this world.

The first node, or sefirah, of the Divine Tree of Life is called Keter, or “crown.” This spot in the flow of Divinity represents something very abstract – a gentle and generative ripple of Divine Will. From there the Divine energy flows from sefirah to sefirah until it reaches the tenth: Malkhut. Malkhut represents the Divine, now transformed and physicalized into countless beings and objects, wave and particle. Malkhut is the world as we know it, but with the added awareness that underneath the illusion of all this separateness and physicality there is the truth of an infinite and permeating Divine. So Malkhut is this Earth. And Malkhut is the Divine energy that permeates and pulses through it. And Malkhut is the close Divine presence that we can perceive in this earthly realm that we call Shekhinah. And Malkhut is us as well—the assembly of the People of Israel, which we can perhaps read expansively as being all of humanity.

So when Esther sweeps into the king’s chamber wearing Malkhut, she is the Earth and she is the Shekhinah. She is Ahashverosh’s kingdom and God’s as well. She is power and sovereignty. She is the majesty of all Creation. And she is the collective of all of us. Her robes are no fashion statement—unless as a statement by no less than the Fashioner of All Creation. (One can only imagine the dazed paparazzi on the red carpet: “Your Majesty, you look divine!”—followed by the mandatory but in this case rhetorical question, “Who are you wearing?”)

Glaringly missing from the Book of Esther is any direct mention of God. By focusing on this use of the word malkhut, our forebears interpret God right back into the story. Not as a purveyor of showy miracles, such as sea partings and salt pillars; not as a human-like personality; but as Malkhut: Divinity that is integrated into everything, if you allow yourself to see it. When Esther enters the king’s rooms, arrayed in the light of Shekhinah, King Ahashverosh has no choice but to see.

Brave and confident Esther was having a moment. She was channeling something big and luminous. How might it have felt to her?

Performers, writers, artists, athletes and even rabbis are familiar to some degree with moments like these, moments of flow. Sometimes, whatever is coming out of you on stage or on paper or on the ball field or the bimah feels like it is coming through you rather than from you. Sometimes, you get through a whole stage show, and everything goes right, and only afterwards do you realize that you had forgotten to worry about your props and your wig and your lines. Or you daven (pray) something beautiful and stirring and afterwards you can’t even remember what you said, except that it left you and the people around you breathless.

I think those moments are ones in which we, like Queen Esther, are wearing Malkhut. We are still ourselves; we haven’t dissolved into undifferentiated nothingness. But there is something of the embedded Divine that is choosing to reveal itself. When we lose ourselves in beauty or in purpose, it is Malkhut asserting itself. And in that state there is much we can do. We can save the people! Esther does.

When Mordecai first tells Esther that the Jews are relying on her for rescue, he says, “u-mi yodea im l’eit kazot higa’t lamalkhut”? “Who knows if it is not for just such a moment as this that you came into the Malkhut? (Esther 4:14). By Malkhut he might have meant simply “the palace.” But how can we not hear in these words a different question: “Who knows if it is not for just such a moment as this that you came into the world? Who knows if it is not for just such a moment as this that you came into contact with Shekhinah? Who knows if it is not for just such a moment as this that you came to be a vehicle of the Divine?”

As we all celebrate Purim this year, donning masks that cover the wrong halves of our faces, staring down a global polycrisis—pandemic, injustice, climate collapse, fascism—we might wonder why we should have been born to see such times. And this year the question asked of Esther presses itself upon us as well. No, we are not queens (well, not all of us). But we are not powerless. We have, each of us, come into the Malkhut—into this complex, glorious, fragile, wounded and still God-soaked world. The odds of any of us having been born are zero. Yet here we are. So maybe we are here in a time such as this because we are here for a time such as this. As Mordecai says, “Who knows?”

Now might be the time to take into account our own masks and disguises and notice whatever personal truth and wholeness is lying behind them, waiting to emerge. How can we tap into Malkhut—the Divine just below the surface—to feel into our purpose? How can we wrap ourselves in a robe of Malkhut and let whatever is intended to flow from us flow? How can we be like Esther: determined, powerful, humble, and full of Shekhinah’s light?

Who knows? Maybe we have all come into the Malkhut for just such a moment as this. So let’s suit up: costumes, wigs, heels, whatever you need to start feeling who you are. Put the script down; you’ve studied it enough. Open yourself to flow and take a deep breath. It’s showtime.

3 Responses

Hi Irwin,

I was looking for a story to tell for the Malkhut section of Rosh Hashanah Musaf. I found your writings on Esther wearing Malkhut inspiring. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. This year, a congregation in Richardson, Texas will be enjoying them. Early Chag samech to you.

What a glorious piece! Thank you for describing Queen Esther in her glory of the Divine Spirit, Shekhinah, Malkhut!

I am not as well-versed in Kabbalah as I’d like to be, but I love the Bible, and you have brought a much deeper reading of Esther to me with this piece. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

I was actually looking for visual images of Esther, and found this, and now I’m very inspired to start my art piece.

Thank you so much for sharing from your rabbinic knowledge and wisdom,, and personal artistic experience!

Todah raba!

Deacon Melissa

(Episcopal)

Dear Rav Irwin,

I was extremely moved by reading your drash, and the idea of being “fully at home in [our skins]” resonates indeed. I will proudly share it with my (mostly senior) congregation here in South Florida, who enjoy the ease of acceptance of different lifestyles. A person can only fully accept the challenges of growing old if they keep an open mind, welcoming the many varieties in which we human beings present ourselves.

This year above all previous, Purim is a challenge. May we Jews find the courage and creativity to share our festivals with all those who wish us well.