Taken from “Shechinah at the Art Institute” by Rabbi Irwin Keller, Blue Light Press, 2024

It’s a cold Shabbat morning in December, and I am sitting vigil at the deathbed of Joseph. I am not alone but surrounded by members of the Taproot Community who have gathered this week in Bolinas, Calif. — Coast Miwok land, on the ocean, in the mist, atop the Pacific Plate, on the other side of the world from Joseph’s Mitzrayim. We are bundled in jackets and blankets, each of us seared on one side by heat lamps like uneven toast. We sit on straw mats in a large, open tent.

The Torah scroll is also down low, close to the Earth. We have a folding table — still folded — lying flat on a Persian rug. The tabletop is wrapped in fancy cloth, and the Torah scroll relaxes gently upon it, draped by an oversized, ocean-blue tallit. Members of the cohort have been leading the morning prayer, and we are now approaching the Torah service and the close of the book of Genesis.

My friend and teacher, Rabbi Diane Elliot, opens the Torah to offer the first reading. When we chanted this same parashah at the Taproot Gathering three years ago, she affected a tremendous tikkun by chanting Dinah back into the blessings Jacob offered his sons. This year, she is reading about the burial of Jacob in the Cave of Machpelah. She shares a midrash that on the journey to Canaan with Jacob’s body, the caravan passed by the pit into which Joseph had, as a youth, been cast by his brothers. Rabbi Diane expounds on the necessity of returning to the places of our trauma for healing to happen. She chants the Hebrew, and our hearts open to the insistent and ancient pain we all carry. When she finishes, we breathe, and several members of the group chant the next verses of Torah.

Then it is my turn to complete Joseph’s story. I have been in relationship with Joseph for years — wondering, puzzling, collecting the many hints in Torah that point to some queerness, some difference in Joseph’s gender. Oddities in the text that gravitate around Joseph’s looks, clothing, emotions, body and social role. His womb that is awakened upon seeing his younger brother Benjamin. His knees that are referenced in connection to birth, in ways otherwise reserved for women of Torah. This has all been churning in my head for years, and a couple weeks earlier, I had even posted a lengthy essay about it on my blog, but I had never chanted any of Joseph’s story from Torah itself. And now I am to chant his death.

I approach the scroll and share some of the things I’ve observed about Joseph. I preview the reading, foreshadowing the verse that tells us that the elderly Joseph’s great-grandchildren were born on Joseph’s knees — a seeming reference to a birthing posture in which a laboring mother braces against the knees of a more senior woman. I explain how I see Joseph at the end of his life — no, at the end of their life — at last being fully at home in their gender, a gender that permits them to be in the birthing chamber with the women. This, just a chapter after the dying Jacob belatedly offers his child Joseph “the blessings of breast and womb.”

The Taproot members are the right group for this Torah. They are cultural healers and spiritual activists, queer or allies, most of them younger than I am by at least a quarter century. Some of them identify and live as non-binary, and use they/them pronouns in their daily life — a choice I, too, might have made if the option were available to me when I was younger. But I feel too old and creaky for that change now, no matter how well it would suit me. I continue to wear my he/him pronouns like a frumpy, ill-fitting cardigan.

As I speak, my eyes wander down to Joseph’s final words in Torah. Joseph offers a prophecy that God will one day remember the Children of Israel and bring them out of Egypt. When that happens, Joseph demands, v’ha’alitem et atzmotai mizeh, “raise up my bones from here.” I had never fully noticed that it doesn’t say, “carry my bones to the land of Canaan,” which would have limited its meaning to the geographic. Instead, Joseph says, “raise up my bones,” without a specific destination identified in that verse.

The word for “bone” (etzem) has metaphoric meaning in Hebrew. It is not only the body’s physical frame, but one’s essence, substance or even self. Joseph’s command can be read as metaphorical: “Lift up my selves.” Suddenly, and for the first time, I hear Joseph asking the Children of Israel — asking us — to raise up, to honor, to carry forward with us, Joseph’s complex and multiple qualities. Their fullness. Their selves.

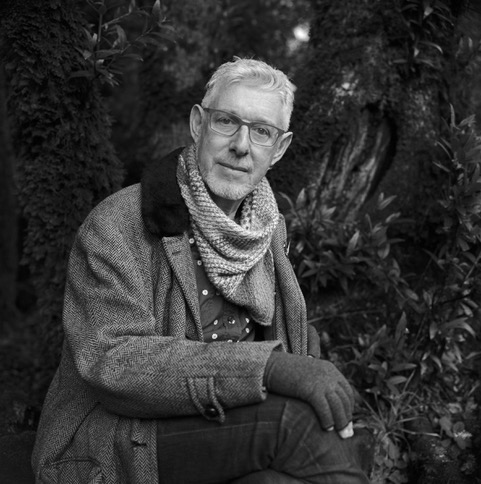

That is what we are about to do, even if it has taken 4,000 years and 7,000 miles to make good on the promise. The group makes the Torah blessing. I chant the melodies I’d practiced — mah’pach, pashta, katon. In my necktie and multi-colored Shabbat skirt, my pulse begins racing. I see how my whole life has led to this moment: my gender journey, my Jewish learning, my queer family, my wounds, my joys, my drag. All of it: preparation.

For the first time, I hear Joseph asking us to raise up, to honor, to carry forward with us, Joseph’s complex and multiple qualities. Their fullness. Their selves.

I reach the phrase about great-grandchildren being born on Joseph’s knees, and I slap my own knees so that we are all together in that anticipated moment. When I reach the last verse, the verse in which Joseph dies, I invite the group to come closer, and they do. We are all on our knees, a tight circle surrounding the Torah as if at Joseph’s deathbed. We are Joseph’s family, the grandchildren birthed on Joseph’s knees. We are standing vigil at the bedside. I grip the Torah rollers, and suddenly, they are Joseph’s hands in mine.

My eyes close as blessing begins to pour out, that we might all be seen in our complexity. That all our bones, our substance, our selves should be uplifted. That we should feel no part of us to be less worthy. That we might see every bit of ourselves and each other as tzelem Elohim — the image of the Divine. I feel tears welling up and hear the quiet weeping of others around me, weeping at the death of Joseph or maybe weeping from the grief of realizing how many parts of ourselves we have considered beneath blessing.

Silence falls. We sit, stunned, as one does after attending a death. Out of the silence comes the voice of one Taprooter, chanting a healing prayer, and we begin singing for Joseph’s healing and for our own. We have all been called to be here in this moment. To witness. To bless. To cry. To heal. Our prayers and blessings pour into Torah, back to Joseph, and we feel blessings pouring forward to us.

We have raised up Joseph’s bones this day, Joseph’s selves. We have raised them right out of the scroll and into our hearts and hands, right into the bright winter daylight of Bolinas, Calif. Chazak chazak v’nit’chazek, we say — the traditional words when completing a book of Torah. “Be strong, be strong, let us strengthen each other.” We dry our eyes, tuck some of Joseph’s sparkling and intricate selves into the pockets of our souls, and look at one another again: aglow, open, knowing.