Winking Across the Ages

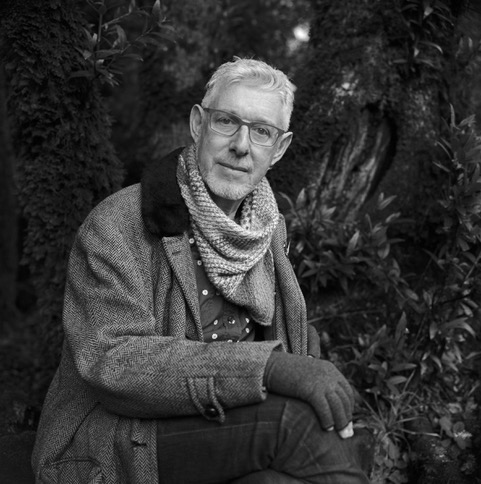

Since childhood, Joseph has been a character who has caught my attention. I identified with him in ways that I didn’t with other biblical characters, ways I didn’t quite have words for. As a child whose gender had to be corralled and corrected, then as a young person who understood himself to be male and gay, and even into an adulthood of reclaiming my own gender difference, I have always seen Joseph in the text, winking across the ages, inviting me to explore more fully the shared elements of our experience.

As it turns out, whenever I turn my attention to Joseph, I see more in the story. Elements that suggest that there is so much more to him than our tradition has allowed. So much more complexity of gender and sexuality. Whether or not he was “gay” as we understand that in our generation, his narrative is a queer one. His role in his family; his role as substitute for his mother and ongoing embodier of her energy; his outsiderness in his family and in Egypt; the bullying he endures; his making good in the Big City; his taking control of his own narrative; and, unlike in a classic hero’s journey, his refusal to return home, instead bringing his problematic family to him, keeping them close but not too close.

There have been times that I have felt self-conscious about reading so much into Joseph. I have felt a fear that I was projecting as a means of locating myself in our ancient texts, and that that was not a legitimate project. But as Rabbi Shefa Gold says, Torah is not about somebody else. I am not projecting myself onto Joseph any more than someone who argues that there is nothing queer about Joseph at all. And while seeing myself reflected in a text feels satisfying and useful and healing, I am not doing this in a vacuum. Joseph invites it, and has been inviting it forever, as we can see from connections drawn by authors of later books of Tanakh and from Talmudic and medieval commentators, connections I will explore below.

Joseph is different in numerous ways in the peshat (plain meaning) of the text. He is his father’s favorite (and for the time being I will use “he/him” pronouns, following Torah’s lead, but without commitment). He wears unusual clothing. He is described as childlike at an age where he should not have been. His beauty is discussed in the text; and in several significant instances there are Hebrew phrases used to describe his appearance, emotion, garb or actions that specifically link him to noteworthy women elsewhere in Tanakh including, repeatedly, his own mother.

What we see in secondary sources – Talmud, Midrash, Targum, medieval commentators – suggests that those thinkers also perceived something unusual in Joseph, and their exegeses gravitate around issues of gender (young Joseph primping his hair) and sexuality (Potiphar purchasing Joseph for his own sexual gratification).[1] These various authors see something about Joseph too, and so they exert effort either to problematize his gender or to explain away problems that exist in the peshat – in the simple text of Torah. In the words of Professor Lori Lefkovitz,

The rabbis are clearly troubled by Joseph’s chaste beauty, but inasmuch as he is a sacred hero, they fear articulating their doubts too directly…. [H]is beauty and innocence strike the rabbis as unnatural and effeminate….[2]

Most striking to me, perhaps, are what seem to be bold hints in the text regarding an atypicality not only in Joseph’s lived gender, but in his (or their) body: the way that the language of “womb” and “knee” gravitate to him in Torah in ways that they do not toward any other men speaks to me of Joseph’s difference.

In this paper, I hope to highlight some of these textual moments, language choices and rabbinic observations, and identify how they point to the complexity of Joseph’s gender.

Joseph’s Sexuality

One straightforward way, as it were, of approaching the question of Joseph’s difference is through a lens of sexual orientation as constructed in 20th Century European and American thought. Through this lens, many elements of Joseph’s biography – his giftedness, his dress, his receiving help from a stranger outside the family system, the bullying of his brothers and his resistance to the sexual advances of Potiphar’s wife – can be harmonized through a view of Joseph as having been gay. This has been explored by Gregg Drinkwater[3] and others.

Even without an academic eye, Joseph’s possible homosexuality is easily picked up on. “Gay Joseph” appears with some frequency in modern popular culture. The Israeli television show Hayehudim Ba’im has aired a series of homophobic sketches in which Joseph is portrayed with a laundry-list of 20th Century stereotypes of male homosexuality. He is limp-wristed. He swishes when he walks. Disco music – that’s the way, uh-huh, uh-huh, I like it, uh-huh, uh-huh – plays whenever he enters a scene. Just to make sure that we understand this is not an affirmative reclaiming, more than one of these sketches culminates in violence against him.[4]

Joseph’s being gay is one possible answer to the question of his resistance to Potiphar’s wife.[5] The rabbinic tradition instead points to Joseph’s affirmative righteousness as manifest in his sexual self-restraint, rather than dwelling on his possible sexual disinterest. BT Yoma 35b discusses how despite Joseph’s beauty and Potiphar’s wife’s advances (which they describe as unceasing), Joseph still found time to study Torah, earning him the label tzadik – “righteous.”

Joseph’s righteousness – and its connection to sexuality – causes him to later be associated in Kabbalistic literature with the sefirah of Yesod – the node in the Tree of Life associated with sexuality and generative properties. It is Yesod that gathers the energies of the five preceding sefirot – including two marked as archetypally male, two as female, and one which, like Yesod, sits on the central column – and joins with them to form a kind of phallus by which Hakadosh Baruch Hu, the male-associated Creator God, can unite erotically with the feminine Shekhinah, located in the subsequent sefirah of Malkhut. The placement of Joseph at the point of Divine sexuality is curious; he becomes the vehicle for sexual union, based on the merit of his having resisted sexual union on the earthly plane. The relationship of Joseph to this sefirah is deserving of much more study with an eye toward Joseph’s gender. But at the least it reinforces the idea that Joseph owns a spot in our collective imagination that is concerned with sex, sexuality and gender.

Princess Garment, Cross-Dressing, Abuse and Beauty

Joseph’s adherence (or non-adherence) to gender norms is called into question early in his story. In Genesis 37:2, Torah says that Joseph was 17 years old, vehu na’ar – “and he was a youngster.” This phrase is technically unnecessary – he is 17 years old; we don’t need to be told whether that is young or not. The fact that Torah tells it, however, suggests that there is some mismatch between Joseph’s age and his youthfulness. Midrash rushes in to explain. In Genesis Rabbah 84:7 we see:

.ואת אמר והוא נער אלא שהיה עושה מעשה נערות, ממשמש בעיניו, מתלה בעקיבו, מתקן בשערו

“So why does it say he was a youngster? Because he engaged in childish things: tending his eyes, lifting his heels, primping his hair.”

The authors of the Midrash see in him a dandy at best, but possibly also someone more deeply transgressing gender norms, either of his time or of theirs. After all, ma’aseh na’arut, “childish acts,” in this line of Midrash could also be read as ma’aseh na’arot, “the activities of girls.” [6] Or perhaps we see some suggestion that childhood affords (or afforded) a wider range of gendered behavior, but by age 17, Joseph should have put away childish things in favor of adult male normativity.[7]

In the very next verse, we learn the most memorable detail about young Joseph. As his favorite, Jacob gives him a special garment – a ketonet pasim – to wear. Something about this long-sleeved or striped garment, sometimes translated as the “coat of many colors,” inflames his brothers’ jealousy and loathing. Drinkwater analyzes the garment as an example of Joseph’s “excess,” perhaps worn to cover up an insecurity about his sexuality.[8]

But one doesn’t need to stray beyond the four walls of Tanakh to understand the significance of this garment. The term ketonet pasim appears only one other place – in II Samuel 13:18, where it says, “She wore a ketonet pasim, for virgin princesses were customarily dressed in such garments.” The context here is the garment worn by Tamar, the daughter of King David. Just verses earlier, Tamar was raped by her half-brother, Amnon, who instantly despised her upon completing his crime, and cast her out. The author of this passage in Samuel certainly knew that its wording would direct the reader back to the story of Joseph and his colorful garment.

Joseph’s brothers also hated him and cast him out, these plot elements living, as in the Tamar story, in close proximity to the mention of the ketonet pasim. This establishes a strong parallel between Tamar’s story and Joseph’s. One element of the parallel suggests that Joseph was wearing a garment designated for princesses. We do not know if this was something he delighted in and requested, or whether it was imposed by his father. Another parallel might be abuse by brothers, and the veiled possibility that Joseph experienced sexual abuse at their hands.[9] This reading would justify adult Joseph’s ostensible plan to get Benjamin away from the brothers, perhaps thinking that Benjamin had taken his spot as the abused child in the family and was in need of rescue. Torah does not ever indicate that Joseph planned to reveal his identity to his brothers; it is only in a spontaneous emotional response to Judah’s polemic beginning at Genesis 44:18 that he does so. What would have happened if Judah were less persuasive? The brothers would have been sent back empty-handed, and the two sons of Rachel would have, at last, escaped the reach of Jacob and sons.[10]

The ancient Israelite world was clearly aware of a range of gender differences and behaviors, even if all that survives in Torah are the attempts to suppress or contain them.

Another possible reading of the parallel between Joseph and Tamar is offered by Rabbi Judith Abrams, who argues that Joseph may have been sexually abused by his father. She goes on to reinterpret all of Joseph’s brothers’ actions as protective – the brothers got Joseph away from their father and told their father that he was dead, holding the bloodied ketonet pasim in hand, so that Jacob wouldn’t go looking.[11]

In explicitly defining a ketonet pasim as a garment worn by the daughters of kings, the second Book of Samuel turns Joseph into a transgressor of gender norms. While we can’t know exactly what norms were in place while Genesis was being written, we know that gendered dressing norms certainly existed in Israelite history. Deuteronomy 22:5 offers a specific prohibition on women dressing like men and men like women.[12] The prohibition is serious; it is called to’evah – an “abomination.”

One chapter later, in Deuteronomy 23:18, Torah prohibits Israelites from becoming kedeishim and kedeishot, a caste of priest/esses called to temple service, perhaps in the worship of indigenous Canaanite goddesses. While this prohibition might be simply about idolatry, i.e. prohibiting participation in non-Israelite and non-monotheistic cultic practices, including serving as cult prostitutes, it might in fact be another attempt to shore up adherence to a clear gender binary. Onkelos translates the verse this way: “An Israelite woman shall not become a servingman (gvar ’aved) and an Israelite man shall not become a maidservant (itta amma).” Subsequent references to kedeishim in Kings and in Job are translated in the vulgate as effeminati. In other words, the kedieshim and kedeishot could have been objectionable because heretical; and/or they could have been objectionable because gender transgressive.

The ancient Israelite world was clearly aware of a range of gender differences and behaviors, even if all that survives in Torah are the attempts to suppress or contain them. So the use of the phrase ketonet pasim in the story of Tamar cannot be innocent coincidence. The author of the Book of Samuel knows that this passage will cause Joseph to be seen as a boy in a princess dress, perhaps a sexually-abused boy in a princess dress. Maybe the author of Samuel is hinting that Joseph’s gender is not a simple matter. Either way, it makes one wonder the degree to which the ire and violence of Joseph’s brothers could be patriarchal retribution for Joseph’s violation of binary gender norms.

It isn’t only Joseph’s clothing and behaviors that are ambiguous. So is his face.

Joseph’s Beauty

The physical beauty of men is rarely mentioned in Tanakh. Saul is described as good and as tall, the combination of which we are meant to understand as attractive. David is described as ruddy, with beautiful eyes, and good to look at. But the specific words describing Joseph’s beauty are noteworthy. We are told in Genesis 39:6, leading into the episode of Potiphar’s wife, that he is lovely and attractive – yefeh to’ar vifeh mar’eh. This phrase occurs only one other place in Tanakh, and that is in reference to Joseph’s own mother, Rachel. In Genesis 29:17, she is described as yefat to’ar vifat mar’eh. It might not be important to know exactly what attributes are described by those words. But it is important to note that Joseph seems to be beautiful in just the way she was, whether that is complexion, shape or poise.

Joseph’s Womb

Later, Joseph’s similarities to or affinities with Rachel seem to come into play again. In Genesis 43, Joseph, now the powerful Egyptian vizier, has maneuvered his brothers into bringing Benjamin to him in Egypt. Joseph sees his younger brother for the first time and is overcome:

וַיִּשָּׂ֣א עֵינָ֗יו וַיַּ֞רְא אֶת־בִּנְיָמִ֣ין אָחִיו֘ בֶּן־אִמּוֹ֒ וַיֹּ֗אמֶר הֲזֶה֙ אֲחִיכֶ֣ם הַקָּטֹ֔ן אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֲמַרְתֶ֖ם אֵלָ֑י וַיֹּאמַ֕ר אֱלֹהִ֥ים יָחְנְךָ֖ בְּנִי: וַיְמַהֵ֣ר יוֹסֵ֗ף כִּי־נִכְמְר֤וּ רַחֲמָיו֙ אֶל־אָחִ֔יו וַיְבַקֵּ֖שׁ לִבְכּ֑וֹת וַיָּבֹ֥א הַחַ֖דְרָה וַיֵּ֥בְךְּ שָׁמָּה

And he lifted up his eyes, and saw his brother Benjamin, his mother’s son, and said, “Is this your younger brother, of whom you spoke to me?” And he said, “God be gracious to you, my son.” And Joseph made haste; for his bowels did yearn upon his brother; and he sought where to weep; and he entered his chamber and wept there. (Genesis 43:29-30)

This is a fascinating and fast-moving passage. Joseph sees his brother Benjamin. Instantly Rachel is invoked – Benjamin isn’t just his brother, he is Rachel’s son. At that moment it is as if the thought of his mother transforms into his mother’s own thought. Joseph impulsively offers Benjamin a blessing, addressing him as beni – “my son” – as if he were Rachel herself.

And then something else happens to Joseph as a piece of this very big moment, but it’s not clear what. Nikhmeru rakhamav is what the Hebrew says. The Jewish Publication Society translates this as “he was overcome with feeling toward his brother,” whereas King James presents an anatomical sense of the phrase: “his bowels did yearn upon his brother.” In doing so, King James leans into the underlying form of rakhamim: rekhem, “womb.”

The Hebrew in this passage is indeed difficult. Is this simply a reference to Joseph’s compassion, divorced from any reference to his body or to gender? Or is there some indication here that Joseph’s response has a physical quality, and a female physical quality at that? Does Joseph have a womb, either anatomically or spiritually? Is his reaction to Benjamin not fraternal but maternal?

Rakhamim is an abstract plural in Hebrew, typically translated as “mercy” or “compassion.” Structurally, it is a plural form built on the underlying singular noun rekhem, meaning “womb.” Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar includes rakhamim among its list of abstract concepts formed as the plural of a closely related singular lexeme. Examples include hashekhim ‘[metaphorical] darkness’, shemanim ‘fatness’, meysharim ‘uprightness’, sha’shu’im ‘delight,’ which are abstractions or intensifications of underlying singular forms: hoshekh ‘[physical] darkness’, shemen ‘fat’, meyshar ‘straight path’, sha’shua’ ‘amusement.’[13] In these cases, there is very little semantic distance between the more concrete singular form and the abstract plural. The connection is self-evident and presumed.

In contrast, there is substantial semantic distance between rekhem, ‘womb,’ and rakhamim, ‘mercy,’ at least in the normative ways the word rakhamim has come to be used in biblical and rabbinic Hebrew. At some point, however, rakhamim must have been closely and self-evidently connected to the idea of womb, gestation and motherhood. Could it be that in the language before us in Genesis, rakhamim is still closely tied to its anatomical source? Might King James have nearly gotten it right keeping it physical, even though its authors felt compelled to make a gender correction, changing “womb” to “bowels” to indicate a pang in Joseph’s belly?

In pursuing this question, I surveyed the use of the root r-kh-m (רחם) in Tanakh, where it appears 133 times. Of these, only 5 instances refer to the physical wombs of identified women: Leah, Rachel, Hanah (twice), and the women of Avimelekh’s household.

Another 28 times it is used as a very close metaphor to mean birth itself, the moment of birth, fertility or the offspring or firstborn of the womb (as in peter rekhem).

Eventually – in 78 occurrences – the root comes to indicate a divine quality of compassion or mercy. Around half of those are in the prophetic books, promising God’s mercy or threatening to withhold it; the other half are in Psalms, beseeching it.

Far fewer – 14 times – are the instances where r-kh-m describes a human quality of compassion. Of those, nine are not individual humans but abstracted human collectives such as nations (e.g. Isaiah 13:18 – “[the Medes] shall show no mercy to children…”). Five instances reveal the human quality of compassion, or arguably the divine quality of compassion expressed through individual humans.

In the Book of Genesis itself, the root r-kh-m only appears six times. Three of these are physical wombs of identified women: Leah, Rachel and the women of Avimelekh’s household. The remaining three occurrences are all connected to Joseph. In Genesis 43:14, when Jacob sends his sons, including Benjamin, to Egypt, he prays that “the man,” whom he doesn’t consciously know to be Joseph, have rakhamim on them. In Genesis 43:30, the passage under discussion here, we find Joseph’s rakhamim being activated upon seeing Benjamin (this reaction being, perhaps, the very answer to Jacob’s prayer sixteen verses earlier). And finally in Genesis 49:25, Jacob, on his deathbed, blesses Joseph with birkhot shadayim v’rakham – “the blessings of breast and womb.” (More on this later.)

The dominant, normative meaning of rakhamim as God’s quality of compassion does not clearly occur in Genesis at all. Instead, there are physical wombs and three puzzling occurrences connected to Joseph.

There are numerous thoughts here for consideration. First, in the evolution of our religious use of the term rakhamim, we have created a broad semantic distance between the quality of divine love and the quality of having a womb or giving birth from a womb. It seems possible that as the Jewish God-concept became more entrenchedly male in antiquity, religious reformers found it important to create greater symbolic distance between “womb” and “compassion.” In other words, as God wandered further from the feminine, so did God’s womb-like, maternal qualities. When, in post-biblical literature, the quality of rakhamim became a human attribute and not only a divine one, the word was returned to humanity with the rekhem expunged from it. So much so that in our day, pointing out the “womb” association of rakhamim feels like a hidush – a creative association and feminist reclaiming, rather than a self-evident etymological connection and clearly intended association.

The loss of the intrinsic feminine in this word is a sore loss. It would not be unreasonable to translate rakhamim – wherever we see it in text, commentary, or liturgy! – as “motherlove” or something else that can capture the actual wombiness at the root of the word, something our ancient Israelite ancestors would have instinctively understood and felt.

Once we see the wombiness in rakhamim, and with our awareness of how limited the distribution of the root r-kh-m is in the Book of Genesis, we can bear witness to Joseph’s maternal ache when he sees Benjamin. This – in a passage in which their mother is remembered and referenced, and in which Joseph calls his brother “my son” – is not a stretch. Joseph didn’t “feel compassion.” His womb ached! – whether or not he physically had one.

This reading of Joseph’s rakhamim as a deep wave of physical, maternal love is supported by the single other appearance of the idiom nikhmeru rakhamim in Tanakh. In I Kings 3:26, we are again in a royal chamber, this time the court of King Solomon. Before him are two women in a dispute. Each has given birth. One of the babies died and its mother swapped it for the other woman’s living child. Each accuses the other of this. King Solomon famously calls for a sword so the child may be cut in two. At that moment the true mother of the living child has a profound surge of emotion:

וַתֹּ֣אמֶר הָאִשָּׁה֩ אֲשֶׁר־בְּנָ֨הּ הַחַ֜י אֶל־הַמֶּ֗לֶךְ כִּֽי־נִכְמְר֣וּ רַחֲמֶיהָ֮ עַל־בְּנָהּ֒ וַתֹּ֣אמֶר בִּ֣י אֲדֹנִ֗י תְּנוּ־לָהּ֙ אֶת־הַיָּל֣וּד הַחַ֔י וְהָמֵ֖ת אַל־תְּמִיתֻ֑הוּ וְזֹ֣את אֹמֶ֗רֶת גַּם־לִ֥י גַם־לָ֛ךְ לֹ֥א יִהְיֶ֖ה גְּזֹֽרוּ׃

The woman whose son was the live one pleaded with the king, for she was overcome with compassion for her son. “Please, my lord,” she cried, “give her the live child; only don’t kill it!” The other insisted, “It shall be neither yours nor mine; cut it in two!”

What is translated in JPS as “she was overcome with compassion” and in King James as “her bowels yearned upon her son” is the exact idiom we see in the case of Joseph: nikhmeru rakhameyha. The actual mother’s post-partum womb is awakened, activated. She feels an ache for her son in the very womb from which he had just been birthed.

This lends support to the notion that whether or not Joseph had a physical womb, his feelings toward his younger brother were definitionally maternal. He, in that moment, stepped into the shoes of his dead mother, Rachel, embodying her and giving voice to her anguish. The writer of the story in I Kings draws that connection explicitly.[14]

Joseph exhibits qualities of motherhood. We have already learned that he had an arguably feminine beauty, and that as a teen he wore a garment customary for daughters of kings. What is Torah trying to tell us about Joseph? Is Torah trying to indicate, even if it doesn’t have quite the words for it, that there is something different, or additional, about Joseph, as the very name Yosef suggests?[15] Is Torah acknowledging that Joseph embodies something we might experience as a feminine energy, or even a feminine physicality, giving us instances of how, even while withholding any discussion of why?

Joseph the Matriarch, and Joseph’s Knees

Two noteworthy events happen later in Joseph’s life. The first is the cryptic deathbed blessing he receives from his father, Jacob. Jacob blesses him with these words:

מֵאֵל אָבִיךָ וְיַעְזְרֶךָּ וְאֵת שַׁדַּי וִיבָרֲכֶךָּ בִּרְכֹת שָׁמַיִם מֵעָל בִּרְכֹת תְּהוֹם רֹבֶצֶת תָּחַת בִּרְכֹת שָׁדַיִם וָרָחַם: בִּרְכֹת אָבִיךָ גָּבְרוּ עַל־בִּרְכֹת הוֹרַי עַד־תַּאֲוַת גִּבְעֹת עוֹלָם תִּהְיֶיןָ לְרֹאשׁ יוֹסֵף וּלְקָדְקֹד נְזִיר אֶחָיו

By the God of your father, who shall help you; and by the Almighty (Shadai), who shall bless you with blessings of heaven above, blessings of the deep that lies under, blessings of the breasts (shadayim), and of the womb (rakham); the blessings of your father have prevailed above the blessings of my progenitors to the utmost bound of the everlasting hills; they shall be on the head of Joseph, and on the crown of the head of him who was separate from his brothers.

Does Jacob know that Joseph’s body is non-conforming, and that Joseph was forced to live in a gender that did not perfectly suit? Might this be a prayer for wholeness?

There are many fascinating and inscrutable turns in this blessing, not the least of which is what the “blessings of breast and womb” are meant to be. This could be a formulaic fertility blessing – but why? Joseph already has children at this point. It could be a blessing that Joseph have the peace he might have had if he had grown up with a living mother. On the other hand, he did nurse at his mother’s breast; if this is the intent of the blessing, it might have been better offered to Benjamin, who knew no mother at all. Might instead this blessing constitute a different and secret healing between Jacob and Joseph?

Does Jacob know something about Joseph’s gender or even Joseph’s physical body that others don’t know? Does Jacob know that there is some way in which Joseph is a woman or like a woman? Does Jacob know that Joseph’s body is non-conforming, and that Joseph was forced (by him? by circumstance?) to live in a gender that did not perfectly suit? And if so, might this be a prayer for wholeness? Maybe Jacob’s blundering and backfiring attempt to accommodate Joseph’s unusual gender as a child by giving him the ketonet pasim is now getting its tikkun, its correction. Jacob belatedly blesses Joseph in the name of Shadai, the breast-nurturing deity,[16] that Joseph might at last find fulfillment and freedom in the body he was given; that Joseph may at last rest easy in “his” womanhood, or in his more-than-just-manhood.

And presto, maybe the blessing comes true. In Genesis 50, we get a last look at Joseph in old age. He has lived to be 110, and, in verse 23 we learn:

וַיַּ֤רְא יוֹסֵף֙ לְאֶפְרַ֔יִם בְּנֵ֖י שִׁלֵּשִׁ֑ים גַּ֗ם בְּנֵ֤י מָכִיר֙ בֶּן־מְנַשֶּׁ֔ה יֻלְּד֖וּ עַל־בִּרְכֵּ֥י יוֹסֵֽף׃

Joseph lived to see children of the third generation of Ephraim, also the children of Makhir son of Menashe were born upon Joseph’s knees (birkey Yosef).

What does it mean that these great grandchildren were born on Joseph’s knees? Like the many other surprising idioms in Joseph’s story, this phrase about children being born on someone’s knees arises only one other time in Tanakh, and again, it is in the story of Joseph’s mother Rachel. In Genesis 30:3 we read:

וַתֹּאמֶר הִנֵּה אֲמָתִי בִלְהָה בֹּא אֵלֶיהָ וְתֵלֵד עַל־בִּרְכַּי וְאִבָּנֶה גַם־אָנֹכִי מִמֶּנָּה

[Rachel] said [to Jacob], ‘Here is Bilhah, my handmade. Go in to her and she will give birth on my knees (birkai) and I will also have children through her.’[17]

What seems to be indicated here is something physical with a social and perhaps legal consequence. In one traditional birthing posture in the ancient Near East, a laboring mother would lean back and brace against the body of another woman, perhaps an elder, while the midwife is positioned to catch the baby.

A woman unable to have children from her own body could (if she had the financial means or social status) arrange a kind of adoption or surrogacy. She would ritually enact this by taking the position behind the birthing mother during the birth. Scholar Robert Alter says, “This gesture serves as a ritual either of adoption or of legitimation,” referring to the social and legal significance of this posture.[18] The child would be considered hers, or under her protection, or in some way incorporated within her legacy. In the few instances Tanakh gives us, there is a power or status disparity between the adoptive mother and the birth mother; we see it with Rachel and Bilhah, and also in the case of Sarah and Hagar, although the “knees” idiom is not used in that case. Even in cases where there was not an adoption or surrogacy, the birth position would nonetheless have involved someone – a midwife or mother or elder woman of the tribe – poised behind the birth mother.

So, the question at hand is whether a text stating that babies were born on Joseph’s knees indicates that Joseph is, socially at least, a woman, or gendered in a way that makes their presence in the birth chamber permissible.

While the use of the b-r-kh root to mean “blessing” is widespread in Tanakh, the use of it to specifically mean “knees” – outside of references to bending the knee in reverence – is remarkably limited. Besides the instances of Joseph and Rachel already noted, there are only 4 other noteworthy occurrences. In Job’s grand lament, he wonders why he was born; why there were knees to push him from the womb (Job 3:12). At Isaiah 66:12, as part of a lengthy prophecy built on birth and infancy metaphors, there is a promise that the people will again suckle on the wealth of nations and be dandled on knees. In Judges 16:19, Samson, whose own birth had been miraculous, falls asleep with his head on Delilah’s knees, while she cuts his hair. And in II Kings 4:20, the Shunnamite woman’s son, whose birth had been prophesied (or maybe brought about) by Elisha, collapses across her knees and dies, in a posture not coincidentally reminiscent of a Christian Pietá – the dead offspring stretched across the once-unwilling womb that had miraculously birthed him, symbolizing unjust tragedy and presaging an imminent resurrection.

Significantly, all these instances of birkayim – “knees” – are references to the knees of women, with the (possible) exception of Joseph. Most of the references are connected to birth, including, in Genesis 48:12, a moment in which Joseph brings forth his sons Ephraim and Menashe me’im birkav – from among or between his knees – to present them to Jacob for blessing. In context, he might be freeing his knees so he can prostrate himself before his father. Even if so, what were Ephraim and Menashe doing between his knees? Is this stance depicted to reinforce a suggestion of female fertility located in Joseph’s body?

As for Joseph’s great-grandchildren being born on his knees: the peshat (plain meaning) of the verse seems to be that Joseph is in fact in the birthing chamber, bracing the laboring mother. If this is so, it suggests that late in life Joseph has come to be a kind of matriarch figure – an elder of the clan who is welcome in the birthing chamber, perhaps again taking the place that would have been Rachel’s. Might Joseph transcend a strict gender binary in a way that was not problematic in its time and place, even though the subsequent commentators found it troublesome?

The commentators indeed find this passage troublesome. They do their best to make it mean anything other than what it seems to say. Medieval commentators Rashi and Ibn Ezra say that Joseph brought these great-grandchildren up on his knees. Luzzato (Italy, 1800-1875) says Joseph received them on his knees after they were born. Targum Yonatan reassigns Joseph as normatively male by translating the passage as Joseph having circumcised them.[19]

Only 14th Century Yemenite Rabbi David Adani, in his Midrash Hagadol on Parashat Vayigash seems to be comfortable with Torah’s words and expand upon them. In his midrash, Jacob’s sons are afraid their father will die of shock when they tell him Joseph is alive. So, they ask Jacob’s sweet-tongued granddaughter, the prophet Serakh bat Asher, to break the news. She goes to Jacob when he is praying and whispers:

יוסף במצרים יולדו לו על ברכים מנשה ואפרים

“Joseph is in Egypt; Menasheh and Ephraim were birthed upon his knees.” [20]

In Adani’s retelling, Serakh reveals a prophecy that not only would grandchildren be born on Joseph’s knees, but Joseph’s own children were.

A Legacy of Visible Women and Absent Men

Rabbeinu Bahya (Spain, 1255-1340) also seems unfazed by children being born on Joseph’s knees. But he is curious as to why it is Makhir’s children who are specifically mentioned in the passage. He proposes that it is because Makhir becomes the great-grandfather of Tzelofkhad, whose daughters – Makhlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milkah and Tirtzah – take up, in Numbers 27:1-11 and 36:1-12, the cause of the right of women to inherit when there are no sons in a family to do so. In Bahya’s eyes, this connection teaches that Joseph was indeed a great tzaddik and in his house were tzaddikim from whom the likes of the wise and righteous daughters of Tzelofkhad would spring.

But there is more here than a legacy of tzedek (righteousness). There is a legacy of women who speak up, women whose stories are told and whose names are uncharacteristically remembered. Does this not, on some level, feel like a kind of tikkun (repair) for Joseph, whose gender difference is not explicitly told and not explicitly remembered?

It is also interesting that the specific petition of the five sisters has to do with the scenario in which there is a legal problem brought about by an absence of social maleness. How might this, perhaps unconsciously on Rabbeinu Bahya’s part, have seemed an important connection to draw back to Joseph? Joseph, arguably, was passed over for inheritance. His sons take up two tribal spots, so his legacy is amply represented – doubly represented in fact. Still, Joseph himself is passed over; we do not speak of a Tribe of Joseph. Ephraim and Menashe inherit directly from Jacob. Is the connection to the daughters of Tzelofkhad a nod toward Joseph’s ineligibility to inherit or to head a tribe because of his own suspect gender; in both stories a lack of social maleness impairing the patrimony?

Transgender? Intersex? Non-Binary?

Joseph’s story and the commentary it elicits are a bouquet of mixed gender signifiers.

It is easy for me to read Joseph through the lens of my own biography. I can spot the femme boy, the sissy, someone who in our era might identify as non-binary or gender-fluid. I see Joseph safer among the women than the men, safer anywhere than with his brothers. I see young Joseph, unseen by his brothers, climbing out of a pit to beg the Midianites for passage to Egypt so that he might at last find his true tribe – not the House of Jacob, but urbane Egyptians who still had a living memory of 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Hatshepsut, one of two documented female pharaohs. I see Joseph – guided by instinct, desperation, prophetic dreams or the whisperings of a knowing stranger – putting his money on his chances in a big city and a new country.

But my lens isn’t the only one. Someone else might see Joseph as a cis-gendered woman, plain and simple. She lives her life in disguise for all the reasons women have lived secretly as men in history. Israeli poet Nurit Zarhi makes exactly this move in her poem, “She is Joseph,” offering an image of Joseph, the little girl, in her mother Rachel’s lap, while Rachel disguises her as a boy:

For she has no son

and her prayers are numbered

and she must lie to her husband, to her husband’s sons.

She must lie even to God.[21]

Such a reading is defensible and dramatic and satisfying. In other ways it is unsatisfying. It reinforces a strict gender binary and gender essentialism – i.e. if Joseph had feminine qualities, Joseph must have been female. This solution allows for no expansive view of gender itself and turns a story of gender complexity into a (simple?) tale of disguise. It fails to capture the expansive and fluctuating sense of gender that pulsates within the Joseph text. Such a solution also begs the question: when Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, why would he drop one disguise and leave another one in place?[22]

Another possibility is that Joseph could have been transgender – that is, a woman whose body was normatively male, forced to live life (with some difficulty) as male. The idea that Joseph was, perhaps, female at the core, is supported by a joint reading of an aggadah in Talmud and a related story in Targum Yonatan. In the Talmudic story, told in BT Berakhot 60a and in Y Berakhot 9:3, Leah, who was pregnant, was concerned about her sister Rachel’s dignity. She had heard a prophecy that Jacob was to have twelve sons. She had already borne four, and the handmaids, Bilhah and Zilpah, had each borne two. If Leah had another boy, Rachel would not be able to bear two boys because they were reaching the numerical quota of boys foretold by prophecy. Leah was determined Rachel should bear at least as many boys as the handmaids. So Leah prayed and the male fetus she was carrying became a girl, Dinah, clearing the way for Rachel to bear a boy. This does not on its own imply that Rachel’s fetus had been female, which would make the story symmetrical. However, Targum Yonatan on Genesis 30:21 tells the same story differently. Instead of Leah’s fetus changing its gender, the sisters’ fetuses were miraculously switched. Robert Harris argues that neither story, nor the reading of them together, requires that Joseph have been female in utero.[23] Nonetheless, the idea hovers in the air. Both fetus-swapping and fetal gender-reassignment feel like potential folkloric explanations for an experience of feeling out of place in one’s assigned gender.[24]

Another possible understanding is that Joseph might have been intersex, i.e. born with physically ambiguous sexual traits. Intersex conditions were known to our ancestors (more than they are known to many people in the modern world, in which intersex children’s genitals are “normalized” surgically and the fact of an intersex child’s difference hidden from others, and often the child itself). The intersex condition called Congenital Adrenal Hypoplasia (CAH) is one in which a child with XX chromosomes and a uterus might also have a clitoris resembling a penis and thus be assigned male gender at birth. A person with CAH could grow to have a mix of secondary sexual characteristics – breasts and a beard, for instance. While (unlike other intersex conditions) CAH can be life-threatening at birth, it is not always so. Children with CAH have survived in every age of human history and are likely the individuals whom Talmud identifies as androginos, among the variations of sexual anatomy Talmud repeatedly takes up.

Note, for instance, this description of androginos in Mishnah, and how well it might fit with our imagining of Joseph. Mishnah says:

אנדרוגינוס יש בו דרכים שוה לאנשים

ויש בו דרכים שוה לנשים

ויש בו דרכים שוה לאנשים ולנשים

ויש בו דרכים שאינו שוה לא לאנשים ולא לנשים

The androginos is in some ways like men and in some ways like women, and in some ways like both, and in some ways like neither.” (Mishnah Bikkurim 4:1)

The Mishnah continues shortly after in the words of Rabbi Meir:

רַבִּי מֵאִיר אוֹמֵר: אַנְדְּרוֹגִינוֹס בְּרִיָּה בִּפְנֵי עַצְמָהּ הוּא

“Androginos – he is a being unto herself.” (Mishnah Bikkurim 4:5).

Here the mixed sexual signifiers of an actual androginos are slyly reflected in the mixed grammatical gender used by Rabbi Meir.

A conclusion that Joseph was an intersex person with CAH harmonizes certain things. The reference to Joseph’s womb would be literal – Joseph has one. His father’s words that he should experience the blessings of breast and womb cease to be metaphoric. At last, Joseph is given permission to value their body as it is. And this, in turn, shifts Joseph’s social gender enough to allow them to be in a birthing room with laboring mothers and midwives, and for babies to be born on her knees.

Pregnancy is also possible for some individuals with CAH, leading to this radical question: what if Ephraim and Menashe emerging from between Joseph’s knees is a subtle (or unsubtle) hint that Joseph in fact bore them?

A gender non-conforming body might also be in the rabbinic mind in Bereishit Rabbah 87:7, which elaborates on the affair between Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. In this version, the two actually make it into bed together, both of them desiring the affair. But then, playing on the wording contained within Genesis 39:11, ve’eyn ish – “there was no man [there]” – it says of Joseph:

ואין איש: בדק ולא מצא עצמו איש

“There was no man: he checked and did not find himself to be a man.” In the moment leading up to consummating with Potiphar’s wife, Joseph checks and discovers he is not a man. The midrash continues, using the archery imagery in Jacob’s testamentary blessing to Joseph in Genesis 49:24 to metaphorically describe Joseph’s sexual impotence. So arguably, on its surface, the midrash is simply saying that Joseph was not a man because he was unable to function sexually as a heterosexual man. Nonetheless, the wording – “he checked and did not find himself to be a man” is tantalizingly suggestive,[25] and could support a reading of Joseph as intersex.[26]

Solving Joseph

Other possibilities remain to be explored. Could Joseph have a female soul? Or could he be inhabited by one – his own mother’s, perhaps, after her untimely death during Joseph’s childhood?

Sixteenth-century kabbalist Hayim Vital writes about male souls reincarnating into female bodies, typically as a punishment for past homosexuality.[27] Later Jewish folklore is replete with stories of possession – girls or women inhabited by a male soul, or dybbuk, in order to explain a young woman’s gender-transgressive behavior. The famed Maiden of Ludmir was spoken of as having been possessed by the soul of a male scholar.[28] And in that story, the vulnerable moment in which the dybbuk entered her body was as she wept and slept on her mother’s grave. The death of a mother seems pivotal in the dybbuk tradition.

Could Joseph have been carrying Rachel’s soul as well as his own? Would this resolve the numerous phrases used for Joseph that would seem otherwise particular to Rachel?

Ultimately, Joseph is not a puzzle to be solved. There is no right answer; there is no detective work that will yield the truth about a mythical figure who might not have inhabited any historical reality. But as a composite figure who holds so much gender non-conformity, it is enough for Joseph to simply be. And to allow Torah its sly allusions to Joseph’s womb, knees, motherliness, feminine garb, feminine beauty and female legacy, so that our attention is drawn, and Joseph may more completely be seen.

For my money, I am happy for Joseph to live their own life, and not the one I wish to impose; a life of expansive and not quite definable gender. I am glad of an ambiguous Joseph, a Joseph who doesn’t fit in the binary and who is beyond the binary. A Joseph whose existence is an invitation for all sorts of queer people to see themselves reflected in Torah’s stories, which too often are not fertile soil for our queer imagination. I have come, in recent years, to include Joseph in my daily avot ve-imahot prayer, as neither patriarch nor matriarch, but holding the space of a trancestor, assuring us that our lineage and our legacy as Jews include figures whose gender is as elusive, illusive and inclusive as our own. For me, right now, that is more than enough.

Epilogue: Joseph’s Bones, December 2021

It’s a cold Shabbat morning in December and I am standing vigil at the deathbed of Joseph.

I am not alone, but surrounded by members of the Taproot Community who have gathered for the week in Bolinas, California – Coast Miwok land, on the ocean, atop the Pacific Plate, on the other side of the world from Joseph’s Mitzrayim (Egypt). We are bundled in jackets and blankets, each of us seared on one side by heat lamps like uneven toast. We sit on straw mats in a large, open tent and daven shacharit (the morning prayer).

The Torah scroll is also down low, close to the Earth. We have a folding table – still folded – lying flat on a Persian rug. The tabletop is wrapped in fancy cloth, and the Torah scroll relaxes gently upon it, draped by an oversized, ocean-blue tallit. Members of the cohort have been leading the morning prayer, and we are now approaching the Torah service and the close of the Book of Genesis.

My friend and teacher Rabbi Diane Elliot opens the Torah to offer the first aliyah. When we chanted this same parashah at the Taproot Gathering three years ago, she effected a tremendous tikkun by chanting Dinah back into the blessings Jacob offered his sons. This year, she is reading about the burial of Jacob in the Cave of Makhpelah. She shares a midrash that on that journey to Canaan with Jacob’s body, the caravan passed by the pit into which Joseph had, as a youth, been cast by his brothers. Rabbi Diane drashes about the necessity of returning to the places of our trauma in order for healing to happen. She chants, and our hearts open to the pain we all carry. When she finishes, we breathe, and several members of the group offer some of the next reading, and some of the verses we offer communally, human-microphone style.

Then it is my turn to complete Joseph’s story.

As you know from this paper, I have been in relationship with Joseph for years – wondering, puzzling about all these oddities in the text that gravitate around Joseph’s looks, clothing, emotions, body and social role. I have thought and wondered and written and talked and taught. But I had never chanted any of it from Torah itself.

I approach the scroll and share some of the things I’ve observed about Joseph. I preview the reading I am about to do, foreshadowing the verse that tells us that the elderly Joseph’s great-grandchildren are born on his knees – a seeming reference to a birthing posture in which the laboring mother braces against the knees of another woman, presumably her senior in age or status. I explain how I see Joseph at the end of his life – no, at the end of their life – at last being fully at home in their gender, a gender that permits them to be in the birthing chamber with the women. This, just a chapter after the dying Jacob belatedly offers Joseph “the blessings of breast and womb.”

Might Joseph be asking the Children of Israel — asking us — to raise up, to honor, to carry forward with us our complex and multiple qualities? Our fullness. Our selves.

The Taproot members are the right group for this Torah. They are cultural healers and spiritual activists, queer or allies, most younger than me by at least a quarter century. Some of them identify and live as non-binary and use they/them pronouns in their daily life – a choice I too might have made if the option were available to me when I was younger. But I feel too old and creaky for that change now, no matter how well it would fit me. So I continue to wear my he/him pronouns like a frumpy, ill-fitting cardigan.

As I talk about Joseph, my eyes wander down to Joseph’s final words of Torah. Joseph offers a prophecy that God will one day remember the Children of Israel and bring them out of Egypt. When that happens, Joseph demands, ve-ha’alitem et ‘atzmotai mizeh, “raise up my bones from here.”

I had never fully noticed that it doesn’t say, “carry my bones to the land of Canaan,” which would have limited its meaning to the geographic. Instead Joseph says, “raise up my bones,” without a specific destination identified.

The word for “bone,” etzem, has metaphoric meaning in Hebrew. It is not only a physical bone, but “essence,” “quality,” “substance” or even “self.” Joseph’s command can be read as metaphorical: “lift up my selves.” Might Joseph be asking the Children of Israel – asking us – to raise up, to honor, to carry forward with us, their complex and multiple qualities. Their fullness. Their selves.

And that is what we are about to do, even if it has taken 4000 years and 7000 miles to make good on Joseph’s request. The group makes the Torah blessing. I chant the melodies I’d practiced – mahpakh, pashta, katon. In my necktie and multi-colored Shabbat skirt, my pulse begins racing. I see how my whole life has led to this moment: my gender journey, my Jewish learning, my queer family, my wounds, my joys, my drag. All of it: preparation.

I reach the phrase about great-grandchildren being born on Joseph’s knees, and I slap my own knees so that we are all together in that moment. When I reach the last verse, the verse in which Joseph dies, I invite the group to come closer, and they do. We are all on our knees, a tight circle surrounding the Torah as if at Joseph’s deathbed. We are Joseph’s family, the grandchildren birthed on Joseph’s knees. We stand vigil. I hold the Torah rollers, and they are Joseph’s hands in mine.

My eyes are on the words of Torah. Then they are closed as blessing begins to pour out, that we might all be seen in our complexity. That all of our bones, our substance, our selves, should be lifted up. No part of us less worthy. Every bit of us tzelem Elohim – the image of the Divine. There is nothing else.

I feel my tears welling up. I hear weeping all around me – weeping at the death of Joseph, or weeping from grief at realizing that there are parts of ourselves that we had considered beneath blessing.

Silence falls. We sit, stunned, as one does after attending a death. One participant begins chanting a healing prayer, and we sing for Joseph’s healing and for our own. We have all been called to be here in this moment. To witness. To bless. To cry. To heal. Our prayers pour into Torah, back to Joseph. And we feel blessing pouring forward back to us.

We have raised up Joseph’s bones today, Joseph’s selves. We have raised them right out of the scroll and into our hearts and hands, right into the bright winter daylight of Bolinas. Hazak hazak venitkhazek, we say – the traditional words when completing a book of Torah. “Be strong, be strong, let us strengthen each other.” We dry our eyes, tuck some of Joseph’s sparkling and intricate selves into our pockets and our souls, and we look at each other again – aglow, open, knowing.

The Epilogue was originally published in the author’s collection, Shechinah At the Art Institute, Blue Light Press, 2024.

[1] BT Sotah 13b.

[2] Lori Lefkovitz, “Coats and Tales: Jewish Stories and Myths of Jewish Masculinity,” in Lefkovitz, In Scripture: The First Stories of Jewish Sexual Identities (2010).

[3] Greg Drinkwater, “Joseph’s Fabulous Technicolor Dreamcoat” in Torah Queeries, Drinkwater, Lesser and Shneer eds. (2009).

[4] Some examples:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a43000jut_M

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UltJNCcgd5Q

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQgRy_zVjHE.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=05ZjVQDtcxY

[5] In discussing the episode of Potiphar’s wife, I am taking the peshat at face value. I do so while noting that heroic accounts of men falsely accused of sexual aggression (Joseph and Potiphar’s wife; Hippolytus and Phaedra) serve a social function of discrediting the lived experience of women and others who are sexually victimized. While being queer doesn’t rule out the possibility of being a sexual aggressor, Joseph’s ambiguous gender and personal history of victimization lend some weight to Torah’s account. And still, an alternative reading in which Potiphar’s wife is telling the truth and is gaslighted is, perhaps, overdue.

[6] This na’arot reading is argued strongly by Robert A. Harris based on comparative references to hair-tending and “stepping” elsewhere in rabbinic literature. See Harris, “Sexual Orientation and the Presentation of Joseph’s Character in Biblical and Rabbinic Literature.” AJS Review 43:1 (April 2019). Harris also notices that even without articulating an explicit view that Joseph’s “childish” activities were feminine, Louis Ginzberg, in The Legends of the Jews, implies it by translating metaleh be’akevo as “walked with a mincing step” – “mincing” being as popular a codeword as “swishing” for implying male homosexuality in 20th Century parlance.

[7] I am grateful to Cantor Jessi Roemer for bringing to my attention the four instances in Genesis 24 in which Rebecca, as a young person, is referred to as na’ar in k’tiv and voweled as na’arah in the q’ri. Was Rebecca’s agency also a gender transgression? Or is this passage pointing to a surprising and Hebrew-defying gender-neutral concept of youth – as in German das kind?

[8] See Gregg Drinkwater, “Joseph’s Fabulous Technicolor Dreamcoat” in Torah Queeries, Drinkwater, Lesser and Shneer eds. (2009).

[9] Note the 14th Century Yemenite Midrash HaGadol which says that Bilhah and Zilpah’s sons would kiss and caress Joseph, cited in Harris, supra at 73. For more about the possibility of sexual abuse by Joseph’s brothers, see Rabbi Dr. Dalia Marx, “Joseph and Gender Complexity,” Rabbis for Human Rights (2014). I also find it interesting that Joseph’s brother Judah only effectuated a tikkun for the wrongs perpetrated on Joseph after he was bested by another Tamar in a sexual episode in which she takes control of his “staff” (Genesis 38). In other words, did Judah have to experience being subject to someone else’s sexual agency and control before he could stand in Joseph’s shoes and bring about healing with him?

[10] Some midrash, for example Genesis Rabbah 93:8, suggests Joseph unmasked himself not because he was persuaded by Judah’s polemic, but because he underlyingly heard a threat that Judah and his brothers would destroy Egypt the way they had painted Shechem with blood. This midrash, however, ignores that Egypt, unlike Shechem, was a mighty and sizable empire. It also denies Joseph’s story its proper denouement by making his reconciliation with his brothers a capitulation to threat rather than a true resolution of the pain between them. The midrashic belief that these tigers cannot change their spots has the additional effect of extending Joseph’s victimhood. It turns Judah’s speech beginning at Genesis 44:18 into cloaked bullying and almost calculatedly denies Joseph his opportunity to be vindicated in the story, robbing him of his hard-earned autonomy and power. I wonder at these rabbis’ unwillingness to see real reconciliation and real redemption in Joseph’s story.

[11] Abrams, “Jacob, Joseph and his Brothers: A Story of Child Abuse?” in Tikkun Magazine Online (Feb. 21, 2014). https://www.tikkun.org/jacob-joseph-and-his-brothers-a-story-of-child-abuse

[12] While the verse prohibits men from wearing simlat ishah – women’s garb – it is not exactly symmetrical. Women are prohibited from wearing kli gever which might be something other than clothing – accessories, tools, weapons. Whatever the exact meaning of kli here, it is clearly meant to prevent the softening of gender distinction. I am grateful to Rabbi Fern Feldman for pointing out this assymetry to me.

[13] Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar (1910) at Section 124.

[14] The use of nikhmar occurs in two other instances. In Hosea 11:8 God says, nikhmeru nikhumai – “my consolation was aroused,” where “consolation” is an emotional or spiritual quality. In Lamentations 5:10, it says, orenu katanur nikhmaru – “our skin glowed like an oven,” where “skin” is pretty clearly anatomical. These two instances neither prove nor disprove the contention that rachamav was chosen in Genesis to signal something specifically maternal if not biological.

[15] In Genesis 30:24, Rachel names her son, saying yosef YHWH li ben acher – “May YHWH add [yosef] another [or a different?] son for me.” Joseph’s name connotes something about “adding on.”

[16] And referencing t’hom, the primordial deep, the Hebrew reflex of the Babylonian goddess Tiamat!

[17] Ibaneh might mean something closer to “I will be built up through her” or “[my legacy] will be established through her.” A play on words between banah, “to build” and banim, “children,” could have been intended.

[18] Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible, A Translation with Commentary, Volume 1, p. 201 fn. 23 (2019).

[19] It might be worth noting that the posture of circumcision is in itself an echo of the ancient birth posture. The sandak, often a grandfather, takes the position of the elder woman in the birthing room. The baby, on the sandak’s knees, is in the place of the birth mother. The mohel takes the spot of the midwife.

[20] I am grateful to Rabbi Fern Feldman for bringing this exciting passage to my attention.

[21] In Jeff Friedman and Nati Zohar, Two Gardens: Modern Hebrew Poems of the Bible (2016).

[22] Or did he? In Genesis 45:1, Joseph kicks the servants out of the chamber behitvada’ Yosef el akhiv – to make himself known to his brothers. What exactly did this revelation or this moment of self-knowledge include? I’m grateful to Rabbi Jay Michaelson for drawing my attention to this phrase.

[23] Harris, “Sexual Orientation”, supra at 87.

[24] I remember as a child thinking alternately that I was meant to have been a girl but something happened in utero, or that born ten days early, I didn’t get to “cook” enough in the womb to become a boy like other boys. I mention this just to point out that it might be not uncommon for people with a gender difference to have associated that difference, at least in childhood, with an event in the womb. These midrashim might be an expression of that reflex.

[25] See discussion in Harris, supra at 79-80.

[26] The same midrash could support a retelling of Joseph as a hidden cis-gendered woman, in an awkward sexual encounter (one pictures Barbra Streisand and Amy Irving in Yentl).

[27] See “Hayim Vital Describes Male Souls in Female Bodies” in Noam Sienna, A Rainbow Thread (2020), and associated references.

[28] See Nathaniel Deutsch, The Maiden of Ludmir: A Jewish Holy Woman and her World (2003).