13. Practice corporeal politics.

Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.

-Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny

Praying With Your Feet

“My feet felt like they were praying.”

— Rabbi Dr. Abraham Joshua Heschel, writing in his diary about marching from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others in 1965.

Timothy Snyder’s premise for writing On Tyranny is that Americans are in serious and imminent danger of living in a fascist state. The 13th of his Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century is “Practice Corporeal Politics,” or more starkly, as I vividly remember from my college years, the question posed at an SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) meeting, “Who is willing to put their ass on the line?”

Successful political resistance requires diverse groups to assemble publicly to demand change. Snyder uses an antigovernment strike in Poland in 1980 as an example of how a broad coalition can demand change. Each section of this coalition previously lost its own individual fight, but by working together, these groups created a labor union and put pressure on the government. The Communist government then outlawed the coalition, but when the government grew weak in 1989, the coalition gained power and helped establish democracy.

His point is that people cannot just disagree with the government. They must actively organize themselves and demand change. This is “corporeal politics” because it requires people to take their bodies outside — and, possibly, put those bodies on the line. If citizens instead passively wait for the government to act, the government will be able to continue gaining power, taking away their rights and shrinking the sphere of what they can keep private.

The shrinking sphere of what is private is also corporeal. The attacks on reproductive rights and gender-affirming care for transgender people are direct infringements on people’s bodies. The attack on bodies has deep roots in America. Kelly Brown Douglas, in her brilliant book, Stand Your Ground, explains how the Black body has been criminalized in the United States. To protect all of our bodies, some of us need to place our bodies on the front line of action.

In America, not all bodies are treated equally. People of color, LGBTQIA people and those with disabilities are in far greater danger of being harmed by police than white-presenting, able-bodied, cisgender folk. While encouraging people to “pray with their feet,” everyone needs to engage in a risk analysis before risking arrest or putting oneself in a vulnerable situation. It is not only police, but increasingly, we need to be aware of right-wing thugs and militia posing a danger.

Corporeal politics is embodying our beliefs by acting on them. It is the integration of mind, body, heart and soul — my feet were praying. I can only be fully authentic to my beliefs if I act on them. At times, that requires going out into the streets and using my presence to communicate the depth of my convictions. It feels powerful to march in the streets with hundreds or thousands of other people singing and chanting. The more diverse the crowd is, the greater my sense that we are breaking down barriers and creating a powerful alternative. For me, it is a spiritual moment of feeling part of a greater whole.

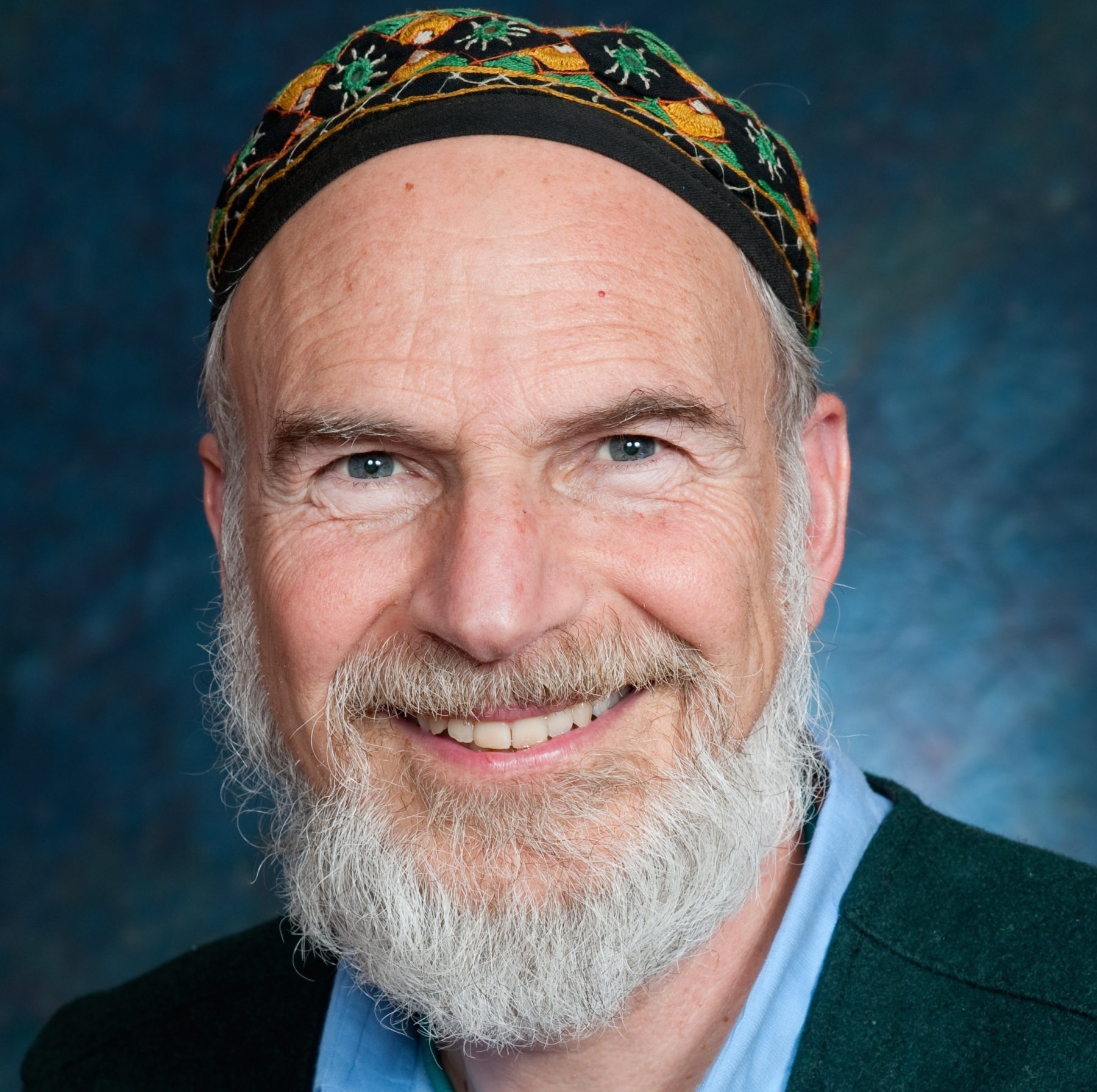

Solidarity is a key element of resistance; dividing us is a key strategy for the right. Nothing says solidarity more than joining a diverse set of people in the streets. Corporeal politics is a very visible venue for demonstrating solidarity. It actively confronts stories of competition, division and scarcity. I make sure that I am visibly Jewish in public actions.

Going out in public can be outside one’s comfort zone, and the more diverse the crowd, the more discomfort some people experience. Experiencing the discomfort is important. We are socialized to obey, to be spectators, to socialize with people who are like us, and in short, to be passive, to be consumers. We need to become citizens who produce democracy. One of the essential teachings of Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi was we must transition from consumer-based Judaism to producer-based Judaism, which is a core Reconstructionist principle as well. The same is true for democracy.

One aspect of corporeal politics is the willingness to risk arrest. As written above, people of different identities run different risks when getting arrested. There are many levels of risking arrest. Many of us are willing to risk arrest when we know that the probability of spending the night in jail is slim and the likely result will be a small fine. Even at that level, the physical experience of being arrested gives one a better understanding of the carceral system and the power of the police. As our political situation deteriorates, the penalties for public demonstrations and non-violent direct action will increase, and other risks will be greater as well. It is already legal in some states to endanger people by driving your car through a demonstration. Some people will make the calculation that taking greater risks is required to stop growing repression.

Going in person to lobby a government official is another form of corporeal politics. Yes, it is good to email, write and call officials, but these actions are less effective and impactful than going in person. I recently had the privilege of lobbying Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) and Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.), each time with a small group of people. Our face-to-face communication was able to surface, for all parties, a deeper level of concern and moral engagement than any written communication could.

We are in election season. Canvassing and knocking on doors is a great way to embody your politics. It allows you to listen and to express what you believe. This is especially true if you engage in deep canvassing, a methodology of how to have extended conversations with the people you meet. To learn more about that, see: https://ctc4progress.org/

I want to address the most challenging aspect of corporeal politics. In 2017, I responded to a call from clergy in Charlottesville, Va., to join them in opposing the “Unite the Right” rally. As a son of Holocaust survivors, I felt it was my obligation to stand up against neo-Nazis and white supremacists/white Christian Nationalists (WCN) demonstrating. Several days before going, the organizers sent an email that there could be violence, even unto death. Sadly, that proved to be true as Heather Heyer was murdered and 49 people injured. I was frightened when I received the email. I was even more scared the night before when, during a church service on the campus, we could hear the chanting, “Jews will not replace us.” The police told us it was unsafe to leave the building; after an hour, we could exit through a back door, but in the distance, we still saw their torches and heard the chanting.

The following morning, about 50 clergy lined up opposite the park where the rally was to take place. Soon, we were face-to-face with hundreds of white supremacists chanting vile slogans; shortly after that, antifa (groups who oppose fascism) arrived. We were at arm’s length from each group, with them shouting at each other. It was evident that violence was about to erupt, and there was nothing we could do to stop it. We extricated ourselves from between the two lines.

I learned many things from that experience. Here, I want to focus on the corporeal aspect. WCNs gain energy being in the streets. A crucial aspect of Hitler taking power was his Brown Shirts terrorizing people in the streets. We cannot cede public spaces to them. This will increasingly be an issue regardless of who wins the 2024 presidential election. We must learn to be in the streets in a safe way. The greatest strategist of non-violent direct action, including resistance to the right, is the late Gene Sharpe. His books are available and widely used around the world. Fascists will win if we cede public spaces to them; that is a proven fact. Hence, we need to put our bodies in the streets.

Hearing, seeing and feeling the intensity of WCN’s hatred makes what they want to do real. It is no longer abstract or theoretical; it is visceral. If they come to power, they will go after the people they hate — anyone who is not like them. Keeping your head down and staying out of sight will not keep someone safe. We already see the kind of laws they will enact.

We need to learn how to manage our fears. Courage is not the absence of fear; it is acting in the face of it. As with any emotion, practicing mindfulness or meditation is helpful. For many of us, it is helpful to do some healing of our inter-generational trauma as Jews. Hearing antisemitic slogans being chanted is highly triggering. None of this preparation can happen all at once.

To protect all of our bodies, some of us need to place our bodies on the front line of action.

One way to manage fear is to go to public actions with a small affinity group.[i] In your affinity group, you can have extended conversations about the level of risk that you are comfortable with and role-play a variety of situations. This will increase your comfort and safety.

Going to demonstrations that may bring up small amounts of fear is a way to start learning how to watch it, manage it and discern the actual danger. It will take courage to stop fascism and risk-taking, which takes practice.

Collective action, through the physical presence and solidarity of individuals, can challenge oppressive systems and create spaces of resistance. Embracing non-conventional coming together of bodies and celebrating diverse expressions of identity can resist fascist attempts to homogenize and control bodies. Engaging in self-reflection, healing and preparation can cultivate courage and ethical consciousness, empowering us to be producers of democracy and promoting inclusive and just societies. Judaism began with Lekh Lekha (“Go forth from your native land,” Genesis 12:1), the embodiment of Abram and Sarai’s courage to leave safety to become exemplars of righteousness. We can do no less.

[i] Affinity groups are self-sufficient support systems of about five to 15 people. A number of affinity groups may work together towards a common goal in a large action, or one affinity group might conceive of and carry out an action on its own. Sometimes, affinity groups remain together over a long period of time, existing as political support and/or study groups, and only occasionally participating in actions. (ACT UP (Aids Coalition To Unleash Power)