The Promise of the Land haggadah is available at www.thepromiseoftheland.com.

A Grand Canyon Seder

The very first Seder I ever led — long before I had thought much about Judaism — was quite elemental. I was in the Grand Canyon on a backpacking trip with a group of geology students. Knowing I would be away over Passover, I had packed a few pieces of matzah and a couple of apples, and some nuts and raisins, to make a simple charoset. On the eve of the holiday, I suggested to the group, none of them Jewish, that since it was Passover and we were in the desert, it would be auspicious and fun to celebrate. They were all game.

I gave everyone a quick overview of the symbolic foods of the Seder, and sent them on their way to explore the land and see what they might find that could signify the ritual foods we needed to help us to tell the story. They returned armed with horehound for bitter herb, miner’s lettuce for karpas (the green vegetable), some skeletal remains licked clean for a shankbone and the cracked shell of a bird’s egg to represent the roasted egg. We found a beautiful spot where the red canyon wall formed an overhang, and as the sun set, we gathered together for a vegetable feast. There, cradled in the most awe-inspiring river canyon with the full moon rising overhead, we sat through the night telling stories — first of the Israelites and then of our own journeys from deprivation to liberation. Everyone participated. It was the most authentic and meaningful Seder I ever attended.

The Earthy Foods of the Seder Plate

Fast-forward 30 years. In the interim, I had pursued graduate studies in environmental studies, taught ecology in high school, run educational wilderness trips and founded Shomrei Adamah, the first national Jewish environmental organization. In 2017, the publisher Behrman House approached me to ask if I would write a Passover Haggadah from an ecological perspective.

It wasn’t immediately clear to me that Passover had a deep enough ecological core to justify a whole new Haggadah. Passover, after all, is pretty human-centered; it tells the story of our liberation from slavery. I thought I would be hard-pressed to find anything ecological in that story. And yet, there were several obvious aspects of the Seder that provided clear connections to the earth:

First, there were the ritual foods. Since that early Seder in the desert, I have always loved the drama of the food on the Passover Seder plate, chief among them: matzah. Matzah is the earthiest of foods — wheat and water — crunchy and dry like the desert. Pesah is even known by the moniker hag ha matzot, “holiday of matzah.” I always felt that matzah, in its elemental simplicity, is the antithesis to the culture of consumerism, a culture of additives, of too much. Utterly simple and unencumbered, matzah sets us free.

Then there was the gnarly horseradish root, standing in for the bitter herb, reminding me of a hidden but exotic life of the underworld. And the karpas — the greens on the table, embodying the vibrant, verdant energy of spring, of life’s urge to break through the dry earth and suggesting that the freedom to just be — to express one’s inner nature — is the most essential freedom. I always tried to embellish the karpas course beyond the conventionally used parsley to celebrate all the greens — the arugula, watercress and cilantro — that sprout from the soil. I’d adorn the table with leaves of these greens as a way to bring the full energy of spring into our celebration. (Along the way, I discovered that some Sephardic Jews have always done this.) And I would expand the time we spent meditating on karpas by adding poems and readings about the meaning of spring and invite my guests to take the time to really revel in it.

And there was the story R’ Everett Gendler used to tell about a potato on the Seder plate to point out how Jews adapted their food traditions according to the environments in which they lived. “Why,” he had asked as a child, “did his family have a potato on the Seder plate when everyone else had parsley?” The answer: There were no greens growing in Northern Europe in early spring to use for karpas. The closest thing to a green vegetable was a potato.

And, of course, there were the plagues — God who had created the whole natural world, was now undoing the creation (in a particular locale) with a series of plagues.

The Meaning of ‘Eretz’

But these, and a few more delightful tidbits, did not seem enough to warrant a whole new Passover Haggadah … maybe a supplement. I felt that in order for me to write an ecologically sensitive Haggadah, I would need a way of understanding the central story of the Haggadah — a passage from the Bible that begins with the words, “My father was an Aramean,” in ecological terms. I spent several months meditating on the passage. I could find nothing ecological about it.

“My father was a wandering Aramean” passage boils the Exodus story down into a few verses (Deuteronomy 26:5-8). It is the most succinct telling of the story of “going from deprivation to liberation” in the Bible. The verses go like this: My ancestors were wanderers. They went down to Egypt. They were bitterly oppressed by the Egyptians. They cried out to God. God heard their cries and led them out of Egypt with signs and wonder. These are the verses that we commonly see in a Reconstructionist, Conservative or Orthodox Haggadah today — and these words are often hidden because they are wrapped inside of an enigmatic midrash. (Some Haggadot no longer even carry these words.)

I had always been bored with this part of the Seder — unable to understand the obscure midrash — and never comfortable with the idea of a triumphant God leading the Israelites out of Egypt. I tended to shy away from a savior theology.

Furthermore, I always wondered, why? Why did God save us? Was there a reason for God’s taking us out of Egypt?

I began doing some research and went back to the Bible to read the passage in context. The rabbis of the Talmud had said that we should read the “entire” passage beginning with the words, “My father was an Aramean.” Suddenly, I realized that there were (at least) two more verses to the passage that got left on the cutting-room floor when the first Haggadot were written down.

The two verses continue: And God gave us a land. And we brought back the first fruits of that land to God.

Hmmm. Here was the clue I was looking for. Why did God free us from Egypt in the first place? God freed us to give us a land, and our job was to bring back the first fruits of the land to God. In a mythical, universal reading of the Torah, our bringing the fruits to God — means giving back our fruits, be they literal or figurative — to God, however we understand God. I understand God as the Oneness of all things. For me, bringing my first fruits to God means bringing my gifts and energy to help care for the earth; for others, this could quite literally mean bringing their fruits to their compost piles to help enrich the earth. We all need to consider what “first fruits” means to us.

The missing verses insist on a reciprocal relationship between God, the people and the land. We return our gifts to God and to the land, and our giving back insures that the land will remain fertile and keep bringing forth its fruits. As long as we keep giving back, the cycle will be unbroken. The land-God-people cycle is attuned to the very cycles of nature.

My reading of this text depends on an understanding of land in universal and ecological terms. Indeed, the word eretz, which is usually translated as land in Torah, also means earth. The 12th-century rabbinic commentator Nahmanides notes that the Hebrew word for “earth,” eretz, suggests a force that causes growth. In other words, the land, the earth is generative; it has a life of its own. Too often in our culture, we think of eretz or land as just real estate or territory — some inert stuff for us to own or conquer. Aldo Leopold, perhaps the first eco-philosopher, writing in the 1940s, defined “land” as an interdependent ecosystem of soils, waters, air, plants, animals and us. The land is a living organism, a community, of which we are a part. The land or earth is our habitat, and we are its inhabitants.

When we understand land — eretz — earth ecologically, then “My father is a wandering Aramean” carries an ecological message.

Of course, many people don’t even notice land in Torah the same way that most of us don’t notice the earth beneath our feet. We associate land and soil with dirt — something to rid ourselves of — never recognizing it as the ground of our being.[1]

The missing verses also teach that freedom means something entirely different than the freedom from our oppressors and freedom from slavery (brought to us by a victorious God). Freedom here means having a land in which to raise our own food and have agency over our own lives. Freedom means living according to nature’s cycles of giving and receiving, and giving back. Our freedom depends on a land that is free from exploitation so that it can continue to flourish and produce its fruits in perpetuity.

‘Hiddur Mitzvah’: The beauty of the mitzvah

Once I felt confident about the ecological dimension of our essential story, I began working on the Haggadah. I hoped my words could capture the poetry I heard in the text and in the land. Yet there were so many things to consider in addition to the text in order to create a Seder that could transmit a more embodied ecological message and reach a wide audience.

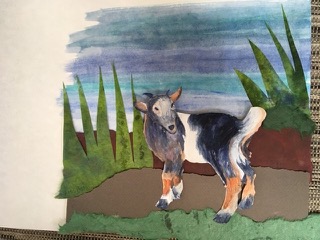

It was important to me that the Haggadah reflect the beauty and wholeness of the natural world. It was my great fortune that Behrman House, the publisher, was as committed to creating a beautiful Haggadah as I was. And through a Google search, we were blessed to find Galia Goodman, a Jewish artist whose work is a reflection of her experience in and appreciation of the natural world. Galia is a dedicated long-distance hiker who had spent her summers section-hiking the entire Appalachian trail. Her work was so perfect for the project that we decided to include a full page of art for each step of the Seder. The art functions as a visual midrash, inviting people to stop, linger and reflect on the images. This was a significant contribution to the Haggadah, since many people are so intent on hurrying through the Seder to get to the meal that they miss many of the flavors and aromas along the path. The art helps people to slow down enough to more fully enjoy this multi-sensory experience. The art and design also helped to weave together the many seemingly disparate pieces of the Haggadah, making it accessible and easy to follow.

Creating a beautiful book was important for other reasons. For many, the experience of beauty can be religious without the sometimes heavy-handed religious language. Beauty is a way of expressing a sense of intimacy with the world, a sense of nearness. Beauty can move people and elevate them in unexpected ways. It offers a way to tap into a reservoir of emotions and motivate people to care. It can provide hope and inspiration in a time when many people are so despairing and exhausted from green fatigue that they don’t even want to hear the word “climate” or “environment.”

Through the process of creating the Haggadah, I came to appreciate how attending to the balance of the verbal and the visual is its own kind of tikkun — the repair of a broken world. Art offers a way to reach those who want to leave behind a purely cerebral way of encountering the world so that they can live more in their bodies and senses. It was also a way to reach children and all those who are more visually oriented.

My ultimate goal was to speak a universal ecological language of text and image to reach across the divides — from the traditionalist uncle who is eager to celebrate Passover in a way that is familiar to him, to the teenager who is struggling to make sense of their Jewish identity, to the shul-goer eager to learn a new kind of Torah, to the secular person who is queasy about religious ritual, to the newcomer who could never understand the anatomy of the Haggadah, to the partners, spouses and friends who are not Jewish and feel timid about participating. I hoped to create a work that was whole and welcoming enough to make space for friends and families who may hold very different beliefs to share the holiday together, while reflecting on the freedom that comes when we embrace our ultimate heritage, the Earth and our connection to her.

[1] But in contemporary times, the word “land” (in a Jewish or Torah context) often brings to mind the modern-day State of Israel. Those who read the Torah literally view the physical land of Israel as God’s unconditional gift to the Jews alone. They consider the land of Israel as the legacy and destiny of the Jewish people. Others consider literal approaches to the idea of “land” in Torah immoral and disturbing, and they may end up dismissing the Bible altogether. Today, the concept of the “land” of Israel has been so fraught politically and religiously that people tend to avoid even considering the ecological meaning of the word. When people understand “land” as territory — to be fought over and acquired and owned, or a commodity to be bought and sold — their view of land invariably becomes economic or political. This anthropocentric and political perspective occludes the deeper ecological and spiritual meaning of “land.”