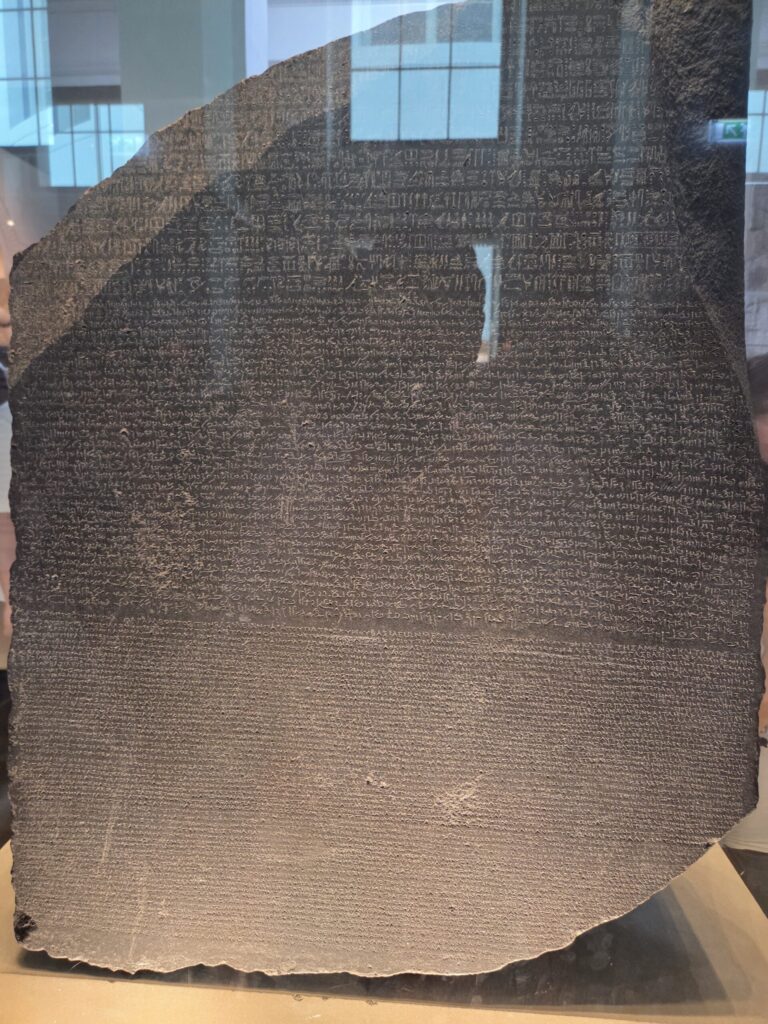

I recently visited the British Museum, and my first stop was to see the Rosetta Stone. Bracketing, for the purpose of this essay, the colonialist enterprise of the British Empire that gathered its treasures from conquered territories, I had never really considered the significance of the Rosetta Stone. Discovered in 1799 by French soldiers and then taken by the British under the terms of the 1801 Treaty of Alexandria, it remains one of human civilization’s greatest discoveries.

As seen here, it has three different kinds of script: Egyptian hieroglyphics (suitable for a priestly decree), Demotic (common Egyptian language) and Ancient Greek. The ability to decipher hieroglyphics had long been lost, but this new find with its trilingual format, enabled archeologists to crack the code of the script here and in many other sites of concern to Egyptologists.

As a translator of the Zohar, the canonical kabbalistic text written in a medieval literary Aramaic, I use dictionaries, commentaries and translations into other languages, and so I was intrigued by the power of this stele to traverse cultures and eras. Of course, the act of translation is not merely about finding word-for-word correspondences from source language to target language; it calls for an understanding of the original in its context, but then also careful consideration of what kind of contemporary product one is trying to produce. Are we trying to translate into idiomatic English in such a way that is wholly consonant with “our” worldview or does one want, somehow, to hold onto the foreignness of the original as a gesture to the impossibility of the task? On the broadest level, are we acquiring or even colonizing in our readings as we force them into terms that are understandable to us, or are we granting them the dignity of being yet another form of human expression?[1] In the second part of Martin Buber’s I and Thou, he talks about the irreducibility of a text (or tradition) as a Thou, and this requires the patience and humility to concede that perhaps we cannot fully understand it.

I begin with this theoretical opening as a caution to myself (and my readers) as I reflect on the ways that I continue to find myself nourished by the Jewish mystical tradition, and by the Zohar, in particular. In this article, I’d like to offer three different areas of kabbalistic lore that have continued to inform my religious thinking and practice over the years. Classical Reconstructionists: Bear with me! Some of the ideas I’m going to discuss are a far cry from Kaplanian thinking or even much of the religious thinking that one finds in most modern discussions of Judaism; still, there are ways in which their difference can shine a light on perennial human issues.

Hasidic writers contend that each individual reveals Torah in a way that is distinctly theirs.

1. Reincarnation and ‘Impregnation’

While questions of personal identity are not new in Western culture of the last half-century, some aspects of identity have garnered particular attention in recent years. To my surprise, I have found that reincarnation, which is not a conventional belief in modern Western thought, is the kabbalistic trope that is most congenial for thinking about identity.[2] The concept of reincarnation started to gain traction in 13th-century kabbalistic works, but in the Zohar, written in Castile mostly in the 1280s and 1290s, it occurred only in the case of someone who did not father (specifically) a child. By the 16th century, through the voluminous teachings ascribed to Isaac Luria, reincarnation came to be understood as the norm rather than a rarity, with each individual slated to continue returning after death to this world until they had fulfilled all of the commandments. If one becomes aware of carrying a spiritual legacy that is quite literally in one’s spiritual DNA, that patrimony can shape one’s consciousness. Suddenly, individual actions are framed in a larger historical and spiritual picture than the conventional “one and done” way in which most Westerners experience their existence.

Stranger yet is a subset of reincarnation called ibbur, literally “impregnation,” whose conceptual parameters would include spiritual infusion or influx. Ibbur commonly refers to the idea that a person’s soul can be a composite of various transmigrated souls. In such a case, the different characteristics or contradictory behaviors that inevitably mark each of us can be understood as a consequence of a spiritual legacy that encompasses a variety of ancient or more recent figures. Sometimes, the presence of an “other” soul is temporary, with a deceased righteous person waiting around in the afterlife for someone to perform a commandment that they have not yet fulfilled. When a living person is about to fulfill that mitzvah, the onlooker zips in for a moment and completes the task vicariously.

Yet another dimension of reincarnation is elaborated by a 13th-century kabbalist named Yosef ben Shalom Ashkenazi (henceforth, RY”A) about whom little personal details are known.[3] One of the distinct features of his approach to the concept is that on account of the fractal-like quality of the natural world — that every species is contained in every other species — as one moves from one cosmic cycle to another, the primacy of one species over another (androcentric in our case) can flip, allowing another aspect of the natural world to dominate. While environmentalists would not be immediately reassured by RY”A’s androcentrism, the fact that in his view, in alternate versions of reality, sure to come in future cosmic cycles, animals, vegetation or even minerals may be the dominant form of existence, yielding a vision that might indeed be congenial to the environmentally-minded. Think Everything Everywhere All at Once as a kabbalistic vision.

One need not take these doctrines literally in order to see them as fecund vehicles for thinking about what it means to be human. As I tell my students about angels, it doesn’t matter whether you believe in angels or not. When reading ancient or medieval lore about them, one finds that angels are good to think with, as a construct that is not quite Divine but also not human. Similarly with reincarnation and ibbur. These are conceptions that premodern mystics developed as ways of thinking about the complexities of human identity, and as such, they break down some of the rigidities in our own thinking about what it means to be human and the nature of our identities.

Kabbalah calls for a dedication and trust that truth can be accessed through the tradition.

2. The Lability of Torah

The notion that there are 70 faces to the Torah may be familiar. This idea first appears in Bemidbar Rabbah, a 12th-century midrashic collection. What’s important about this dating is that it appears to correspond with the first appearance of kabbalistic thinking in Provence, so that many ideas that are developing in kabbalah make their debut in this midrash. History aside, the apparent pluralism of the midrash finds its mythical home in the multivocality of kabbalah. By the time we get to 16th-century Tzfat, the Torah has 600,000 faces, corresponding to the paradigmatic number that came to represent the number of Israelites in the desert. It’s not a far jump to the truly subjective stances that we find among Hasidic writers who contend that each individual reveals Torah in a way that is distinctly theirs.

To be sure, neither the rabbis nor the kabbalists nor the Hasidim were thinking that Torah should be enacted or interpreted with the kind of subjective freedom that people celebrate today. Nonetheless, the tracks were laid for modern approaches that validate individual choice. For me, whether in my Orthodox community or my Reconstructionist workplace, it is a reminder of the hazards of inflexible thinking or the insistence on dogma. At the same time, the freedom that kabbalah seems to be offering is constrained by the principles that were important to its authors and transmitters.

There is a famous passage from the Ra’aya Meheimna, a late stratum of Zoharic literature, that reads:

At that time, There did He set him a statute and law, [and there He did test him] (Exodus 15:25) — these are the Masters of the Mishnah. Here, too, They came מרתה (Maratah), to Bitterness (Exodus 15:23), the Oral Torah returns to them in bitterness, with great exertion, in poverty, fulfilling through them And they made their lives bitter with hard work (ibid., 1:14) — this is קושיא (qushya), Talmudic difficulty. With mortar (ibid.) — with קַל וָחוֹמֶר (qal va-homer), a fortiori. And with לבנים (levenim), bricks — with לִבּוּן הִלְכְתָא (libbun hilkheta), clarification of the halakhah. And every work in the field — this is בָּרַיְיתָא (baraita), [literally,] external teaching. All their crushing work that they performed — this is תיקו (teiku), unresolved. (Zohar 3:153a, Ra’aya Meheimna)

This passage repeats itself a number of times with variations in this late Zoharic stratum, clearly expressing a dissatisfaction with Talmudic learning. Taking each of the terms of Egyptian oppression as code for Talmudic key-phrases seems to suggest a rejection of the Talmudic edifice. But in a different though no less representative passage from this author we see another teaching that qualifies this disdain:

… one who instigates the removal of kabbalah and wisdom from the Oral Torah and the Written Torah, preventing people from delving in them, declaring that there is only peshat of the Torah and the Talmud — certainly it is as if he has dammed up the flow from that river and from that garden. Woe unto him! Better that he should not have been created in the world and that he should not have learned Written Torah and Oral Torah! He is judged as if he had returned the world to chaos and void, brought poverty to the world, and extended the exile. (Tiqqunei Zohar 43, 82a)

For this kabbalist, there is a certain sincerity of intent, devotion and piety that are essential keys for turning laborious study into Divine delight. Ultimately, the Talmud and its mystical path can be best understood with reference to the lyrics of the kids’ song “Going on a Bear Hunt”:

Can’t go over it,

Can’t go under it,

Can’t go around it,

Got to go through it!

What kabbalah calls for is a dedication and trust that truth can be accessed through the tradition. It is not a denial of historical meaning, but rather a quest for mythical meaning, a truth that is not reducible to the “Egyptian” building blocks of history. For folks in our time, through the adoption of Paul Ricoeur’s “second naiveté,” one doesn’t dispense with historical truth, it’s just that one doesn’t stop there.[4] In other words, historical scholarship and creeping historical secularization have made the founding stories (“myths”) of many religious civilizations difficult to accept in a literal sense. But what post-modern (and/or post-secular) thinking does make room for is attachment to those myths as psychic paths to regaining a sense of the sacred in our lives. Indeed, the word emunah (faith/belief) is etymologically related to the word immun, alignment. Thus, “belief” shifts from the need to affirm the historicity of an event or some metaphysical system to an affiliation, loyalty and commitment to those stories and structures.

Kabbalistic fellowships formed as a way of gathering intensely spiritually minded individuals who were committed to pious religious devotion and personal growth.

3. Finding Community through Mystical Fellowships

One of the key structuring blocks of Jewish societies influenced by kabbalah is the formation of fellowships, often called confraternities. These groups formed as a way of gathering intensely spiritually-minded individuals committed to pious religious devotion and personal growth. Often, they imagined that their energetic connection and commitment could eventuate in grand historical or even cosmic achievements. The best known of these groups include the fellowship surrounding Isaac Luria (the Ari or Arizal, 1534–1572), in 16th-century Tzfat;[5] the circle around the Italian kabbalist Moshe Hayyim Luzzatto (Ramhal) in the early-to-middle 18th century;[6] Ahavat Shalom, in Yeshivat Beit El in Jerusalem headed by Yemenite kabbalist Shalom Shar’abi in the mid-18th century;[7] the fellows of the Hasidic figure R. Avraham Kalisker in Tiberias in the late-18th century;[8] and conventicles projected by R. Kalonymous Kalman Shapira (1889–1943), commonly known as the Piaseczner Rebbe, and then later as the rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto.[9] These groups interest me as a subset of larger society in which people of penetrating insight and sincere dedication constructed infinite relationships while working towards a quest of peak spiritual attainment.

All of them, to some extent, based themselves upon the havrayya, the mystical fellowship described in the Zohar, led by the second-century Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai (Rashbi). Taking its cue from the 2022 Oscar-winning movie, Everything Everywhere All at Once, Rashbi and his companions are depicted as living in the second century in the Galilee, while being written about in 13th-century Spain, and perhaps reflected a confraternity that actually existed in Castile during the time of its composition. The author, through imaginative ventriloquism, imagined himself voicing the spiritual aspirations of another, from another time and another place. The latter-day groups then engaged in a similar kind of imaginative time-space reorientation, trying to live out the lives lived on the pages of the Zohar. Lines that divide eras, geographies, identities, human and text all dissolve in the pursuit of an expanded consciousness.

The intensity and intimacy of the interactions of the members of the Zohar’s fellowship can be seen through a characteristic greeting: “When the Zohar’s rabbis arrive at the home of R. Pinhas ben Yair, he steps out and kisses R. Shimon, commenting, ‘I have merited to kiss the Shekhinah (feminine aspect of God)! How exalted is my portion!’ ” (Zohar 3:59b). Imagine if every time we greeted a close friend, we saw them truly as a manifestation of Shekhinah!

These historical groups drafted Community Contracts to which each member had to commit themselves. Among the items often stipulated were love for the other; concern about each other’s spiritual and material welfare; a havruta-style pairing in which the duo would meet regularly to talk about their spiritual growth-edges, challenges, accomplishments and failings; and the encouragement to offer constructive rebuke as a way of keeping the group streamlined in its religious dedication. Much like these groups did, a number of years ago, the faculty and students at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College drafted a list of Community Commitments that would be read and studied together annually with the student body with the aim of enhancing solidarity around common cause. The Kabbalists and the Hasidim were urged to view the entire Jewish people as limbs of a single cosmic body, and to regard their fellowship, similarly, as composing essential components of a single unit. While at the College, the Community Commitments did not formulate the same metaphysical preconceptions about the significance of the student body, the goal nonetheless was to inspire that sense of unity, common cause and the vital nature of their mission.

Imagine if every time we greeted a close friend, we saw them truly as a manifestation of Shekhinah!

Conclusion

I started to study Kabbalah in 1988 in Jerusalem while I was a full-time rabbinical student at Yeshiva University’s campus there. During the day, I was studying the Talmudic tractate of Bava Batra and the laws of kashrut, but at night I was inhaling the works of Gershom Scholem and began my learning of medieval Kabbalah. A year later, I began my doctorate in Jewish studies, specializing in Jewish mysticism. For 30 years, I have taught various texts of Kabbalah at the RRC and continue to find its malleability, aspirations and myths inspiring. And, on top of the themes that I’ve described above, a final motivator is the paradoxicality that lies at the heart of Kabbalah. Every day, at different stages of my morning prayer, I recite the following Kabbalistic kavvanah: “For the sake of the unification of the blessed Holy One and His Shekhinah, in reverence (literally: fear) and in love, in love and in reverence, to unite the name Yod Hei Vav and Hei in full unification, in the name of all of Israel.” The liturgical doubling — “in fear and in love, in love and in fear” attempts to evoke a paradoxical yoking of opposing emotions because it is trying to point us to a place that is not easily reducible to common language. The religious aim of this paradox is to motivate us to strive to be bigger than we are, kinder than we are, more loving than we are and more committed to right behavior than we are. May we rise to the task.

[1] See Daniel Boyarin, Judaism: The Genealogy of a Modern Notion (Rutgers University Press, 2018) for a discussion of these issues as he explores the appropriateness of the term “Judaism”.

[2] The best resource to learn about reincarnation in Judaism is the recently published The Life of the Soul: Jewish Perspectives on Reincarnation from the Middle Ages to the Modern Period, eds., Andrea Gondos and Leore Sachs-Shmueli (State University of New York Press, 2025).

[3] On this figure and his doctrine of reincarnation, see Jonnie Schnytzer in ibid., pp. 151–176.

[4] See Paul Ricoeur, The Symbolism of Evil, trans. Emerson Buchanan (Beacon Press, 1967), p. 351.

[5] See Lawrence Fine, Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos: Isaac Luria and His Kabbalistic Fellowship, Stanford University Press, 2005, especially, 300–58; Roni Weinstein, “Kabbalistic Innovation in Jewish Confraternities in the Early Modern Mediterranean,” in Nicholas Terpstra, Adriano Prosperi, and Stefania Pastore, eds., Faith’s Boundaries: Laity and Clergy in Early Modern Confraternities (Brepols, 2012), pp. 234–247.

[6] See David Sclar, “Perfecting Community as ‘One Man’: Moses Hayyim Luzzatto’s Pietistic Confraternity in Eighteenth-Century Padua,” Journal of the History of Ideas (Jan 2020), pp. 45–66.

[7] See Pinchas Giller, Shalom Shar’abi and the Kabbalists of Beit El, Oxford University Press, 2008; Lawrence Fine, “A Mystical Fellowship in Jerusalem,” Judaism in Practice, Princeton University Press, 2001, pp. 210–14.

[8] See Zvi Leshem, “Mystical Confraternities: Jerusalem, Tiberius and Warsaw: A Comparative Study of Goals, Structures and Methods,” in Hasidism, Suffering and Renewal: The Prewar and Holocaust Legacy of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, eds., Seeman, Reiser and Mayse (State University of New York Press, 2021), pp. 107–130.

[9] Ibid.

3 Responses

I enjoyed this very much so, well written and explained. Thank you!

Joel–I found the article difficult, challenging and enlightening. It brought back good memories of my time at RRC and of the things I learned while studying with you. What a great way to start off my Friday morning!

Yishar koach, Joel. And thank you for continuing your sacred work of making the wisdom of Kabbalah and Zohar accessible to a new generation.