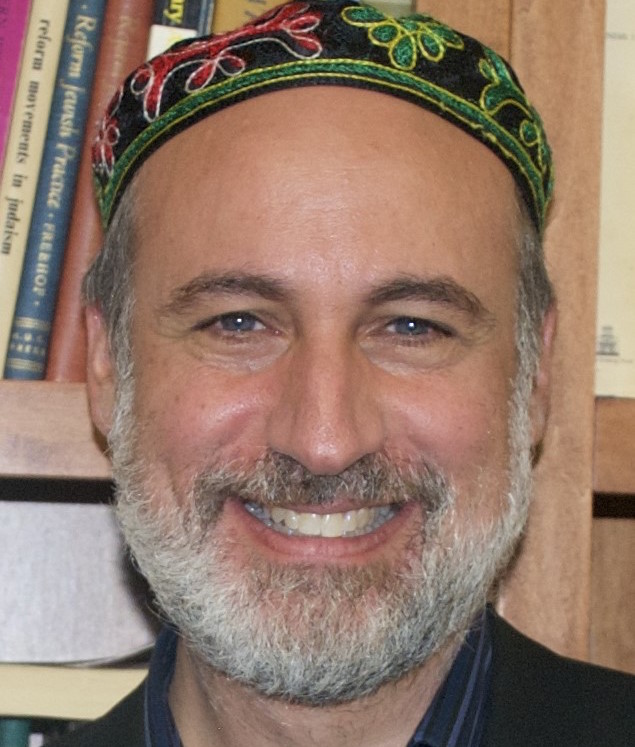

Rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb outlines the five pillars that serve as a base for the Jewish environmental movement: sufficiency (dayenu), resilience (kehillah), responsibility (akhrayut), justice (tzedek) and hope (tikvah).

“No justice, no peace,” we chant at many rallies in this age of rampant injustice. Every bit as true, but far less pithy, would be: “No steep reduction in our carbon footprint, no justice; no radical rethinking of our values and practices, no peace!” The paucity of good green slogans reflects the diminished urgency many of us sense around what we nonetheless acknowledge to be a true climate crisis.

Ecology holds an odd place in our spiritual activist consciousness. In well-educated communities (including most of Jewish America), environmental awareness is a given; we acknowledge the hole in which we’re digging ourselves, ever deeper. But where our time and resources really go, where there’s critical mass for activist tikkun olam (literally “repair of the world”) efforts, ecology rarely ranks. Polling data bears this out – American Jews are unusually likely to support the scientific consensus that human-induced climate change is a major and growing threat, yet quite unlikely to find it imminently and personally relevant.[fn]Public Religion Research Institute, November 2014. 78% of American Jews believe climate change to be a crisis or a major problem, while only 14% predict that they will personally experience substantial harm from its ravages. (https://www.prri.org/research/believers-sympathizers-skeptics-americans-conflicted-climate-change-environmental-policy-science/)[/fn]

Every issue is important! We must never accept the frame, imposed by some rightists and leftists alike, that various vectors of tikkun olam are in perpetual competition with one another for scarce attention. Rather, they’re all interconnected. How can we tackle poverty or structural racism, without addressing the disproportionate environmental impacts borne by marginal communities? How can we advance global justice and sustainability, without addressing gender (in)equality?

We often affirm with Emma Goldman and Dr. King that “none are free until are all free,”[fn]Emma Lazarus, in 1883: “Until we are all free, we are none of us free”, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who wrote “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” in his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” often advanced the same sentiment. (https://jwa.org/media/quote-from-epistle-to-hebrews)[/fn] and “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Likewise, none are secure from the ravages of a changing climate and denuded world, until all are secure. And given the clear and growing scope of those climate impacts – which exacerbate every challenge, from hunger to refugees to illness to political instability and violence – climate change lies near the center of the tangled web of issues on which we each work.

So, to recycle the name of this initiative: we need to evolve, fast.[fn]The assignment from Rabbi Jacob Staub: an entry on the “Doing Justice Work Jewishly” section of Evolve (an initiative whose very name reflects Mordecai Kaplan’s homage to Charles Darwin and empiricism!), “coming at environmental action from a Jewish perspective — which texts can ground us, which values do we uphold, which hopes do we cherish, etc.” My intellectual and spiritual debt to Dr. Staub, and to all my teachers and classmates at RRC (1993-97) and elsewhere, suffuses this essay.[/fn] Our thoughts and actions must get in step with the true scale of what humanity is bringing upon ourselves. Luckily, our tradition – especially its forward-thinking branches, which are ever reconstructing Judaism – offers a treasure-trove of perspectives, teachings, and resources for our collective journey towards where spirit meets sustainability.[fn]A similar spirit suffuses the recent writings of Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman, President of Reconstructing Judaism. At the dawn of her extended effort to articulate “resilience” as our watchword amid the current political climate (31 January 2017), she wrote: “The Jewish people and the Jewish civilization have survived over 3,500 years and in ever-changing circumstances. We have a deep capacity for resilience in the face of setbacks and even catastrophe. We can and should draw deeply on this rich treasure house of resilience and renewal. “The Jewish ecological movement has demonstrated that we are deeply interconnected with all human life, as well as the planet on which we make our home. Moving forward, we must emphasize the cultivation of empathy, the building of relationships and coalitions, finding ways to foster our interdependence. This will require practice and self-scrutiny and a willingness to be vulnerable. Again, Judaism has much to teach us and much that will support us in this work.”[/fn]

Let’s consider five core values, drawn from the heart of our sacred tradition, each of which points to actions we can and must take. All are offered in the spirit of the final value, tikvah/hope – hope that we can embrace sustainability not just as a needed survival tool, but as a spiritual way of life, as second nature, as sacred opportunity. Let’s tikkun this olam (repair this world), together, pronto.

Sufficiency (Dayeinu)

The most-remembered word of the Pesach seder is also a watchword for the 21st century: Dayeinu, “it is [was] [would be] enough for us.”

Beneath today’s environmental crisis is a crisis of values. We’ve traded our birthright of clean air and water for a mess of material porridge. Most care for the valuations of stocks, and their stockpiles of stuff, over the biosphere on which all life depends. The Earth’s carrying capacity cannot (and with pervasive poverty does not) support 7.3 billion people at upper-middle class American early 21st levels. Large climate-controlled homes, many meat meals, frequent flights, cars wherever and whenever, massive wardrobes!? – we’re not entitled! Beyond bal tashkhit (the oft-cited command to not waste), our consumption needs cathartic cuts.

To really extend kavod (honor) to everyone, we consumer-polluters must develop an ethic of sufficiency, which includes: (1) “Dayeinu.” (2) Shabbat, our weekly retreat from the rat race of extraction-production-consumption-disposal, favoring happy sustainable activities like fellowship and song, prayer and poetry. (3) The core meaning of sacrifice/korban, from sacred/karov – giving up material things, for far greater spiritual benefit. And (4) the Mishnah, איזהו עשיר–השמח בחלקו. “Who is rich – whoever is happy with their lot”.[fn]Mishnah Avot 4:1, attributed to ben Zoma.[/fn]

Progressive Jewish values already prefer common-wealth to individual affluence. We must jettison more “stuff,” whittle down our ecological footprint ever further, in order to increase the world’s joy and justice.

Resilience (Kehillah/Shmita)

Kehillah is community, not “resilience” per se[fn]Just as “resilience” is a newly-popular concept in English, it’s barely attested in Hebrew. Dr. Cindy Dolgin, in preparing a graduation address on resilience, found two possibilities: “The first is ‘kvitziyut.’ A kvitz is a spring or coil that when pressured, bounces back, so I guess that ‘resilience’ in Hebrew is ‘springiness’. The second definition is “kosher hittosheshoot,” or the ‘ability to recover.’ And, in the Megiddo Dictionary, right after the noun ‘resilience’ comes its adjective, ‘resilient.’ Resilient in Hebrew is ‘gamish’, which means ‘flexible’…” (http://www.ssdsnassau.org/news/hos-hs-graduation-address/)[/fn]. Yet communities powerfully help their members bounce back – preventatively, through strength, health, and education; and reactively, through presence, support, and shared resources. Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman, who leads our movement in which community is central, holds that “Judaism, writ large, is about resilience”[fn]Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman, 15 Aug 2017, https://ejewishphilanthropy.com/keeping-the-faith-resilience-in-the-jewish-tradition[/fn] . Resilience and community go hand-in-hand.

Jewish resilience is clearest in shmita (‘release’), the biblical sabbatical year. Despite dubious details, shmita is our asymptote, the tall goal we seek to approach ever more closely. It rolls ecology, social and economic justice, communal resilience, sustainable agriculture, and personal spirituality into one interconnected whole.[fn]Key reads in the movement which puts shmita at the center: Yigal Deutscher’s incredible Envisioning Sabbatical Culture: a Shmita Manifesto; writings by Rabbis Arthur Waskow and David Seidenberg, among others; Hazon’s great organizing efforts, including introductory materials and a bibliography; and “Shmita Yisraeli,” led by Drs. Einat Kramer and Jeremy Benstein, among others. In a Reconstructionist pulpit context, see my series of Adat Shalom High Holy Day messages before (outlining shmita’s interconnection of values), during (on food and on ‘cross-training’), and after (on community/hakhel) the most recent shmita year of 5775 / 2014-15; see also this 01/22/2018 episode of Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman’s Hashiveinu podcast.[/fn] Shmita (with yovel/jubilee) lets the land rest and regenerate, protects workers and servants, frees slaves, annuls debts, restores equality, decenters private ownership, ensures small interconnected communities, protects immigrants and the poor along with wildlife, keeps population reasonably low, and favors a higher quality of life over higher GDP.

Shmita is the grand unification theory of progressive Judaism! In today’s imperiled world, “shmita-consciousness” might be among Judaism’s greatest gifts.

Responsibility (Akhrayut)

The Sierra Club’s motto – “Explore Enjoy Protect” – is a modern eco-version of Deuteronomy 8:10: “You ate; You were satisfied; You bless.” In both cases, we can’t just take in the world’s bounty; moved by our experience, we must give back, materially and spiritually. This is responsibility.

Alan Morinis describes Mussar, the Jewish approach of ethical contemplation, in ecologically-sound terms: “Take responsibility, it says. If you made that mess, clean it up. Better still, foresee the mess and take responsibility before it happens, so there won’t even be a mess”[fn]Alan Morinis, Everyday Holiness; Boston: Trumpeter Books, 2007; pp. 205, 203, 200.[/fn]. This goes equally for the mess in our household, our town, or our world – in each case, as the Talmud insists, we’re responsible.[fn]Talmud Shabbat 54b: כל מי שאפשר למחות לאנשי ביתו ולא מיחה – נתפס על אנשי ביתו, באנשי עירו – נתפס על אנשי עירו, בכל העולם כולו – נתפס על כל העולם כולו “Anyone able to protest against [the transgressions of] their household, and does not, is punished for the actions of the members of the household. Against [transgressions of] their townspeople, is punished for the transgressions of the townspeople. Against [transgressions of] the entire world, is punished for the transgressions of the entire world.”[/fn]

“The material needs of another are an obligation of my spiritual life,” wrote Mussar master Israel Salanter; Simcha Zissel Ziv of Kelm called this “bearing the burden of the other.” Today’s others include climate refugees, victims of rising seas and strengthened storms, those hungry from longer droughts, and so on. Justice delayed, via our glacial progress in addressing climate change, is indeed justice denied.

We in developed nations, wealthy from centuries of exploiting nature and people alike, must take real responsibility for climate mitigation (reducing emissions), and adaptation (lessening adverse impacts). The only other outcome is suffering, of which much is already locked in, and more yet depends on how quickly we mitigate and adapt[fn]John Holdren, then White House science advisor, in 2010: “It’s really that simple: mitigation, adaptation, and suffering. We’re already doing some of each… The question – the issue that’s up for grabs – is what the mix going forward is going to be among mitigation, adaptation, and suffering. If our aim is to minimize suffering, as it should be, as it must be, we’re going to have to maximize both mitigation and adaptation.”[/fn]. Per Mussar, carbon neutrality and adaptation assistance are now core spiritual goals.

Justice (Tzedek/Mishpat)

Our many words for ‘justice’ fall on a spectrum – hesed / loving-kindness; tzedek-tzedakah / righteousness; mishpat / right relations; din / legal judgment[fn]This spectrum of “justice” – as outlined jointly by Rambam, Malbim, and Samson Raphael Hirsch, among others – is helpfully laid out in an Etzion Yeshiva shiur by Yitzchak Levi. https://www.etzion.org.il/en/jerusalem-%D6%A0city-justice-and-kingship[/fn]. Each bears new meaning in the Anthropocene, our climate-imperiled era: Love, guiding all our actions. Interpersonal righteousness, measured and expressed by reducing our ecological footprint. Right relations, not just among people, but between humans and the rest of Creation[fn]Jeremy Benstein recommends adding bein adam l’svivato, relationships between a person and their environment, to tradition’s relational categories of la’Makom (with God) and l’havero (interpersonal). David Seidenberg’s important 2015 Kabbalah and Ecology (Cambridge University Press, 2015)) focuses on our relationships with and responsibilities toward non-human nature.[/fn]. Environmental regulations and laws, defended and strengthened, to protect all we hold dear.

Climate considerations loom large – again, mitigation and adaption – in our redifat tzedek, pursuit of justice, as mandated in Deuteronomy 16:20. Further green nuance comes through the question of time scales: “Certainly much social-change activism needs to respond to immediate needs,” notes Rabbi David Jaffe, while expounding on savlanut/patience. “At the same time, lasting social change often takes years if not decades. How do we engage in fixing the world while holding a perspective that our efforts could take generations?” [fn]David Jaffe, Changing the World from the Inside Out; Boulder: Trumpeter Books, 2016, p. 145. Jaffe’s entire work should be required reading for Jewish activists.[/fn] Indeed, thinking intergenerationally is thinking ecologically.

Two of God’s thirteen attributes (Exod. 34:6-7): “extends lovingkindess to the thousandth generation;” “visits sins unto the third and fourth generation.” The bad news? Carbon emitted today will continue to wreak atmospheric havoc for about a century, some three or four generations – so we now imperil our own great-grandchildren, scientifically as well as spiritually speaking. The good news? Loving-kindness lasts orders of magnitude longer.

Hope (Tikvah)

We close with the hardest, most important value. How to affirm hope given climate science, obfuscation, backsliding, and mounting suffering?

Start with Dr. Anthony Leiserowitz’s “Five Big Facts” – “Scientists agree. It’s real. It’s us. It’s bad. But there’s hope!” [fn]Yale’s Dr. Anthony Leiserowitz, presentation to Citizens’ Climate Lobby (video plus written summary), June 2017 – a fine summary of findings from the key emerging field of climate messages, and it behooves all activists to know the “six audiences” characterized by varying attitudes toward climate change: “alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, and dismissive”. Good communication starts with asking “Who are they? Where are they starting from? What are their underlying values? Who do they trust? Where do they get their information? Then and only then can you really be effective at trying to engage them.”[/fn] Acknowledging the complexities, and citing data behind each terse truth, he expounds: “Our job is to convey these ideas effectively, so that the conversation around climate change becomes one about solutions and hope.” One concrete example? Some 21 million Americans have joined, or appear willing to join, a campaign to convince elected officials to take action to reduce global warming. “By contrast, the NRA is around 4 million. Think of the influence an organized group of 21 million climate champions could have!”

As Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman and I have publicly discussed, this is all resilience (a word with positive connotations). “Instead of focusing on [our] hot, crowded, denuded world, we can focus on the resilient potential within nature and within us,” [fn]Rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb, in dialogue with Rabbi Dr. Deborah Waxman, 22 January 2018 – as recorded on https://hashivenu.fireside.fm/7 – transcript available there as well[/fn] to become more effective, hope-filled climate communicators.

Again, to keep hope alive, we must keep our eyes on the intergenerational prize – thinking long-term, ala Dr. King’s long moral arc of the universe, helps greatly. Other sources of hope abound in our sacred texts, like Isaiah 57-58 (the Yom Kippur Haftarah)’s promise that once we enact true justice and sustainability, our light shall “break forth like the dawn.” And Hatikvah, seventy-year-old Israel’s national anthem, references the Jewish people’s “2000-year hope to be a free people in our land” – a microcosm of today’s global hope, that all people may dwell, securely and sustainably, with the land.

***

These are just five briefly-outlined values, from among the countless gifts our tradition can bestow upon those doing the most literal sort of tikkun olam / global repair. Let’s keep turning tradition around and around, applying all that’s within it to the “fierce urgency of now” which compels our caring for Creation, from generation to generation.[fn]“Turn it around and around, for all is contained within it” (ben Bag Bag, Mishnah Avot 5:2). “Fierce urgency of now” (Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.) reflects the many – e.g. NAACP environmental justice champion Jacqui Anderson, Rev. Dr. Gerald Durley, and more – who now see climate change as the civil rights, as well as social justice, cause of our time. And the tag-line “Protecting Creation, from Generation to Generation” went with the Coalition on the Environment and Jewish Life (www.coejl.org), one of many groups with whom to ally, and places to go for further learning and action – with www.InterfaithPowerAndLight.org, www.nrpe.org, www.hazon.org, www.GreenFaith.org, www.CanfeiNesharim.org, www.neohasid.org, www.ShalomCenter.org, https://RAC.org/environment, http://www.heschel.org.il/heschelen-media, and many more in the Jewish, interfaith, and secular environmental realms.[/fn]