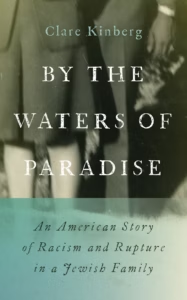

[Excerpted from Claire Kinberg, By the Waters of Paradise: An American Story of Racism and Rupture in a Jewish Family, Wayne State University Press, 2025]

For forty years, I tried to find my Aunt Rose, my father’s sister. I hadn’t known she existed until, as a young teen, I began to feel her presence as an occasional shadow in my family’s life. My father’s brother and sisters were the tall oaks in the little woods of my childhood. Our family (my parents, my four siblings, and I) and my father’s extended Ashkenazi Jewish family (his siblings and their children and grandchildren) lived in connecting neighborhoods. We saw each other at least monthly at our rotating Sunday socials, during which we had dinner, and the women played canasta while the men played poker, and the kids dashed in and out of rooms. I grew up secure in the knowledge that the Kinbergs of St. Louis were a proud and loyal clan. I had no idea that one of the trees had been walled off into a separate garden.

When, at age twelve or so, I overheard my father preparing to take a short trip, I barely noted it as a curiosity. Dad was standing in the doorway to the kitchen of our split-level home in suburban St. Louis County. The light was behind him, and his face was in shadow. Even though I was looking at him, I didn’t see him. My mother was behind him, and I heard her say that Dad was going to Vandalia to see his sister Rose. This information was so unexpected and out of place that, like a jigsaw piece that obviously didn’t fit into the puzzle I was just beginning to assemble, I put the information aside. I didn’t even examine the possibility of another aunt for several years. I didn’t ask any questions. With a child’s blink, I filed away the knowledge that there was a Rose in Vandalia.

I came of age in a nuclear family of white-flight early adopters during the paradigm-shifting years of the Civil Rights Movement. When my father heard, in 1962, that a Black family had moved within a few blocks of our near-to-the-city suburb, he began the search for a new home as far west in the county as he could afford.

My father’s family had been moving west, block by block, for two generations. The Kinbergs’ St. Louis experience matched the well-worn American urban narrative of Jewish neighborhoods becoming Black neighborhoods when the Jews moved out. The related history of Jewish family-owned businesses staying in the old neighborhoods even after the Jews left also fit my family’s story.

My father’s sister Rose was an exception; her life did not follow this pattern. After she left St. Louis in the 1930s, she moved into a segregated Black neighborhood in another city with her African American husband and ended up living the rest of her life on the shore of a small lake in a rural Black community.

Aunt Rose and I grew up a generation apart among Ashkenazi Jews whom I had been raised to believe were completely segregated from African American families. But the separation was both a lie and a truth so deep it was invisible even as it was enforced. Despite Jim Crow and antimiscegenation laws, and despite racist social conventions, racial borders were commonly crossed.

I grew up secure in the knowledge that the Kinbergs of St. Louis were a proud and loyal clan. I had no idea that one of the trees had been walled off into a separate garden.

Both Aunt Rose and I lived our adult lives with Black people. My wife is descended from enslaved Black women and their white owners, and our adopted daughters were born of Black women in the United States. For me, being in an interracial family has meant navigating persistent racial segregation and living intimately with the effects of racism on those closest to my heart.

Because of its impact on my daughters, I am conscious of how race operates in every interaction I have. Like a woman walking alone at night considers her safety, like a Jew reading the daily news with an eye to evidence of antisemitism, awareness of race and its implications for my family never leaves me. But I’m still learning what to do with my awareness of the dangers. As a woman, I’ve learned to clench keys in my fist, ready to deliver a powerful defensive punch. As a Jew, I’ve internalized the need to keep a bag packed, ready for the historically predicated

need to escape.

Growing up in my birth family and my neighborhoods, I did not acquire the insight or tools to cope with anti-Black racism; rather, I learned how to perpetrate it. But for the racism of my family of origin, I might have grown up knowing Aunt Rose and knowing her husband’s family as

machatunim (Yiddish for the in-laws’ family). If Aunt Rose had been part of our lives, part of my memories—the stories that shaped my future—I would have been grounded at a younger age in a deeper truth of how the caste system works in America.

• • •

My Aunt Rose died on my twenty-seventh birthday, February 6, 1982. I know that now because I found her death certificate on the internet in 2016, thirty-four years after she’d died. I was sixty-one.

In a flash, a doorway to Aunt Rose’s life opened on my screen. She had resided less than two hours from where I lived in Michigan with my wife, Patti, and our two daughters.

Seeing Aunt Rose’s death certificate, I felt a flood of regret that I hadn’t found her while she was still alive. I became determined to find her burial place. I was awash with wonder at the coincidence of her closeness to me.

My search for Aunt Rose’s life was made easier because she herself had provided the information on her death certificate. Though she didn’t know—or remember—her mother’s maiden name, she usefully included the name of the funeral home she intended to have take care of her body and the cemetery where she was to be buried. The funeral home still had a slim manila folder for her that contained an obituary from the Cassopolis Vigilant: “Born in St. Louis, Missouri, there are no known survivors at this time. Several close friends looked after the deceased during her illness.” The obituary implied that her friends did not know whether she had family or how to contact them. Did she keep her birth family hidden from her friends, or did she ask her friends not to reveal her birth family? Reading “no known survivors at this time” confirmed that her separation had been permanent and created new possibilities and conundrums for me. Perhaps she’d anticipated that one day a niece would come looking for her.

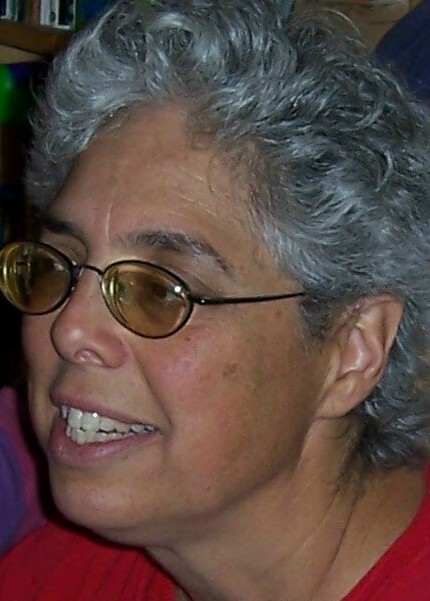

Despite my long career as an editor of a Jewish feminist political and literary journal, when I stood on Aunt Rose’s unmarked grave, I felt for the first time that I had to become a writer because I needed to tell her story.

The book I imagined told a story about Rose Kinberg alongside another story about her husband, Zebedee Arnwine. Their separate stories would merge for a while and then separate again. I wanted to tell a story of how a non-Jewish (my presumption) African American man and

an Ashkenazi Jewish woman had tried to make a life together against and amid generations of genocidal racism and antisemitism. I wanted to record my search for my Aunt Rose’s life and what I could find of the people she knew and the places she’d lived. By writing this story, I knew I

would need to examine my own interracial family life, my Jewishness, my choices.

Before Aunt Rose and Mr. Arnwine met, they’d lived for more than twenty-five years in their separate communities— she with immigrant Jewish parents in St. Louis, and he in a family of Black farmers in Muskogee, Oklahoma. I’ve located records showing Mr. Arnwine had already been married three times and had three children—one with each of his wives—prior to his marriage with my Aunt Rose. Aunt Rose, too, had married young and had a child before divorcing. Sometime during the Great Depression, my Aunt Rose and Mr. Arnwine moved to Chicago together without their young children.

When Aunt Rose died in 1982, I had recently met Patti, the woman who would become my life partner. Patti and I both wanted children. I have lived my life as a lesbian and feminist activist while being active in the Jewish community. I have moved many times: from St. Louis to the rural Ozarks, then to Brooklyn, Seattle, and Eugene, Oregon, finally settling in Ypsilanti, Michigan, where Patti and I raised our daughters. Social segregation along racial lines prevailed in every location. Patti and I never found the racially integrated Jewish community we sought and tried to create, though we have formed lasting friendships in each place. Our daughters grew up within the pervasive and unsettling atmosphere

that our family did not fit within society’s dominant lines.

Despite Jim Crow and antimiscegenation laws, and despite racist social conventions, racial borders were commonly crossed.

I began my search with questions I knew would defy answers. In what ways was Aunt Rose an outcast, in what ways a rebel? What could explain the different choices made by my father and by Aunt Rose? Without talking directly to them, how would I find out where Aunt Rose and Mr. Arnwine met, why they bought land in southwest Michigan? Did she regret leaving her son, Joey, behind? What were Aunt Rose’s reasons for staying in Michigan when, after twenty years, she and Mr. Arnwine divorced? How did she feel about her decisions? Would she have wanted to meet me?

Not long after I found Aunt Rose’s death certificate and obituary, I located another piece of evidence of her life in the 1940 federal census, which showed that Zebedee Arnwine and his wife Rose lived in Chicago at 5168 South Michigan Avenue. Everyone on the census page, including Aunt Rose, was coded “Negro.” Aunt Rose was coded as working in the home, and Mr. Arnwine as working as a huckster for a vegetable dealer.

With these documents, I felt encouraged that with determination I could find more. While working part-time gigs from my cluttered home office and parenting our teenage daughters, I researched and wrote in the corners of my life. It took years just to find three pictures of Aunt Rose. Unexpectedly—after six years of working on this memoir—I learned that Aunt Rose’s younger sister, my Aunt Gertie, kept a private diary during 1933, the crucial year of Aunt Rose’s separation from the family.

Writing my aunt’s life was an inward-facing process: Though a generation distant, her background is my own. I could hear her sisters’ voices, my father’s inflections. I listened for echoes within to imagine Aunt Rose.

To write Mr. Arnwine’s life, I searched directories, public legal documents, and census records. These shards of his life led me to buried scenes of American history and, specifically, Texas and Oklahoma history. Deep in the archives, I found stories of dispossession, violence, and vulnerability that shaped the contours of my aunt’s and Mr. Arnwine’s lives. The same themes also shape my own twenty-first-century life.

My Aunt Rose and Mr. Arnwine lived together before, during, and after World War II. This context grabbed me by the throat. They lived with tensions that still echo in my world.

During the war, they bought land on the shore of a small resort lake “reserved for colored people” (according to a county road map published in the 1940s) in Vandalia, Michigan. Paradise Lake had been a covert from brutal racism for over one hundred years, which nurtured what I think of as quiet streams of an iconoclastic, antiracist culture. Their community was not an oasis, but it was racially subversive and necessarily functioned autonomously from most of the country. My Aunt Rose had chosen a life apart from her birth family. On Paradise Lake, she had found a makom, a place; a miklat, a refuge; and a mistor, a hidden place to settle. These biblical Hebrew words resonate throughout this story.

On one of my first visits to Vandalia, I found a street named Arnwine running through a small neighborhood of homes on the south shore of Paradise Lake. Later, I found the deed to the twenty-five acres on which those homes were built, and then a document that had allowed the county government to build a road down the middle of the acreage. The land Aunt Rose and Mr. Arnwine owned with Arnwine Street running down the middle had been platted as the “Arnwine Shores” subdivision. With these facts on the ground, I felt I had found the cornerstone to

this story. A place. Aunt Rose had owned a piece of land and had named it.