Through practicing gratitude and recognizing the complexities of privilege, we are better suited to pursue the work of changing the world.

My family has benefited tremendously from the professional and nurturing childcare provided to us by the caregiver who has worked in our home. And I became involved in the campaign for the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in appreciation for the contributions she has made to my family over these years, and all the time, energy and loving care thousands of other caregivers have provided to other families. These hardworking individuals have long deserved the same respect that any other professional deserves.

On a sweaty day in August of 2010, Donna Schneiderman spoke these words with audible emotion in her voice. As a member of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ) in New York City, she was speaking to express her support for the first ever Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights in the United States. It was a historic moment for social-justice movements internationally, and it was a moving expression of Donna’s gratitude for her employee. As a working mother of two, Donna’s gratitude for the care her domestic worker provided her children brought her nearly to tears every time she spoke about it. I had the joy of witnessing her deep feelings frequently during our involvement in the campaign together. Her gratitude was powerful, and it motivated her in her pursuit of justice. My experience organizing with JFREJ, and other Jewish and multifaith organizations over the years has shaped much of my thoughts about who we are as Jews and how we do the work of making the world a more just place.

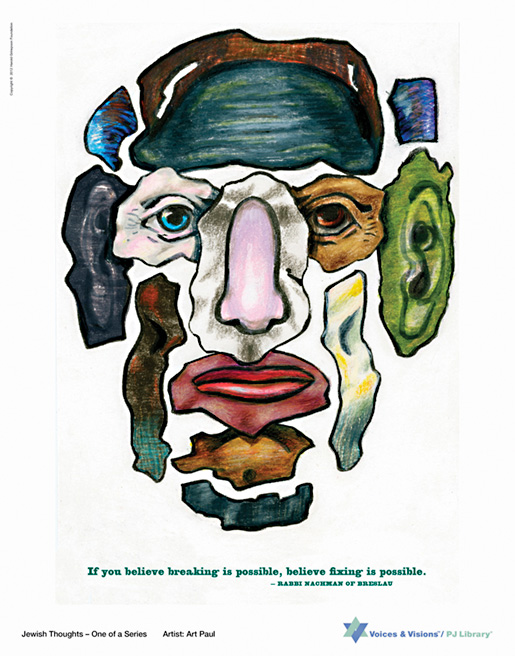

As a people, we have many stories of suffering and oppression: our enslavement under Pharaoh, the destruction of our holiest sites by the Babylonians and the Romans, the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Shoah—the list is long. It is no surprise that much of our people’s reasons for being involved in social justice work come from our people’s stories of suffering. This is also reflected in the theology that motivates most of our justice work today. The term tikkun olam is a nearly universal phrase among liberal Jews and even extends beyond the Jewish community. While having varied origins, it is most commonly understood in relationship to its kabbalistic heritage, referencing the spiritual work that we need to do to repair the brokenness that was part of God’s creation of the world. The theology itself emerged around the time of the Spanish Inquisition—a particular time of persecution and violence in Jewish history that the kabbalists explored theologically and spiritually. Tikkun olam has offered a meaningful theological framework for me and for countless other Jews. It has helped us understand that our justice work is also spiritual work; that God desires us as partners in this work; and it helps us imagine a world redeemed. As Reb Nachman of Breslov teaches, Im ata ma’amin sheyekholim lekalkel, ta’amin sheyecholim letaken/“If you believe that [the world] can break, believe that [we] can fix [it].” Tikkun olam gives us the gift of hope.

Tikkun olam also has its drawbacks. As a theological metaphor, it focuses our attention on the painful pieces of our lives and our communities. While this is helpful in that it draws attention to that which is in need of repair, this particular focus has a spiritual and emotional impact on us. Focusing primarily on brokenness can be a painful and unsustainable way to be in the world. It shapes how we live and how we do the work of building movements for justice. My hope here is to offer another way. It is not meant as a substitute, but rather as a supplement. Tikkun olam has offered us a powerful way to do the work, and I want to suggest that Jewish tradition offers us another path. This is the path that Donna Schneiderman embodies in her speech. This is the path of halleluyah. If the path of tikkun olam heightens our awareness of what needs to be repaired, the path of halleluyah helps us to discern the joys of being liberated.

This passage from the Mishnah (familiar to some as a central piece of the Passover Haggadah), while about the experience of Israelite oppression, invites us into just about every Hebrew word for joyfully expressing our gratitude to God for bringing us into freedom. Halleluyah then, is the summative word to encompass all of the possible praising, lauding, glorifying and thanking that one can do. This Mishnah asks us to respond to social advancement with gratitude. For many of us, myself included, the common response to our own material gain is either to act like it is the normal course of events or to respond with guilt. Our tradition disrupts these tendencies and calls us into a place of gratitude, joy and halleluyah.

While Torah frequently recalls ki gerim hayitem, that “we were strangers” as an impetus to love the stranger, this Mishnah refocuses our attention not on the oppression we experienced, but on the experience of liberation. We find this as well in our liturgy for Friday-night kiddush, which tells us that Shabbat is a zekher litziyat Mitzrayim—“a reminder of the Exodus from Egypt”—not a reminder of the oppression but a reminder of our liberation. The difference is subtle but significant. By focusing on our suffering, we risk exactly that—focusing on our suffering. We risk being self-centered, exclusively self-protective and lacking compassion for others. The ancient rabbis and our tradition demand more of us. They demand halleluyah.

Halleluyah, while focused on the blessings and privileges of life, is not without its rough edges. The first halleluyah appears in Psalm 104, which provides us some insight into what the word might mean for us today. According to the Talmud (Berakhot 9b), “[King] David said one hundred and three [Psalms], but he did not say ‘halleluyah’ in any of them until he saw the downfall of the wicked.” Only then could David say ‘halleluyah’ wholeheartedly. As it is stated, “Let sinners cease from the earth, and let the wicked be no more. Bless the Lord, my soul, halleluyah!” (Psalms 104:35). Similar to yitziyat mitzrayim, this vision of halleluyah reminds us that our own freedom has often come at the cost of others. Whether it is the death of the Egyptians in the Red Sea or the sinners ceasing from the earth, we know that our own material successes have been possible because of the suffering of others. The assimilation of Ashkenazi Jews in the United States into whiteness and its accompanying privileges was only possible because we were able to distance ourselves from black folks and other people of color. The public schools I attended growing up in the suburbs of Philadelphia were extremely well-funded because of funding channels that prevented sufficient funds going to other schools just blocks away in Philadelphia proper. The very laptop with which I write these words was made by a company recently accused of using child labor in its supply chain to mine cobalt by hand in the Congo. Halleluyah is not about simplicity; it is about complicity. It allows us to be deeply, tremendously grateful for our privilege, for our education and for our material possessions, and it demands that we work against the very systems that brought us that complicit privilege in the first place. By politicizing our gratitude, we have the option to not be complicit.

Halleluyah does not have to come at the expense of others. As the discussion in the Talmud continues, we encounter another reading of the verse from Psalm 104 offered to us by the ever-wise Torah scholar, Bruriyah. The Gemara relates a story that Rabbi Meir (Bruriyah’s husband) was being harassed by some local hooligans, which caused him great anguish. In response, he prayed for their death. Bruriyah knew better. She said to him, “What is your thinking? On what basis do you pray for the death of these hooligans? Do you base yourself on the verse, as it is written, ‘Let sinners (Chotim-חוטאים) cease from the earth” (Psalms 104:35), which you interpret to mean that the world would be better if the wicked were destroyed? But is it written, ‘let sinners (Chotim-חוטאים) cease?’ No! [Rather,] ‘Let sins (Chata’im-חטאים) cease,’ is written. One should pray for an end to their transgressions, not for the demise of the transgressors themselves” (Berakhot 10a). Bruriyah offers us a midrashic reading of the Psalm that radically transforms its meaning. She goes on to teach that rather than praying for their demise, Rabbi Meir should pray for them to repent. Bruriyah’s reading of the verse leading up to the first halleluyah in Tanakh radically reimagines what halleluyah could mean. Rather than a world in which we imagine our own oppressors drowned in the sea or ceasing from the earth, we can imagine a world in which oppression ceases from the earth. Then we would surely sing halleluyah.

In a historical moment in which Jews in the United States on average earn more money than any other religious group, we need a theology that is not primarily about brokenness. This is not to say that there are not also poor Jews or Jews who are oppressed in other ways like racism, transphobia and ableism. Tikkun olam can and should continue to resonate with us. For some of us, it may be frightening to forge a politics that does not come from the furnaces of our brokenness. We may not be people with significant wealth or privilege. My hope is that the idea of halleluyah offers an antidote to the hyper-individualist culture that we live in. Being part of the Jewish people means being able to see beyond our own personal pains and understand ourselves as part of a people with thousands of years of history. On both Hanukkah and Purim, we recite a brakha (“blessing”) with the line, “who made miracles for our ancestors in their days, in this time.” This brakha draws our attention not to the good in our own lives, like so many brakhot do, but to the good in our ancestors’ lives. Regardless of our emotional, material or spiritual state, we express gratitude for events thousands of years ago. Our gratitude need not even come from our own direct experiences but can come from the history of our people. If we get in touch with what it means to feel gratitude for our people surviving government plots for our decimation, rather than focusing on the fact there have been attempts at our decimation, what spiritual and political possibilities open up for us as a people? A politics of halleluyah, grounded in gratitude and praise through action, could change both our world and ourselves.

Salo Baron, the Polish-born scholar of Jewish history, argued that “suffering is part of the destiny [of the Jews], but so is repeated joy as well as ultimate redemption.” Baron opposed the notion that Jewish history was simply one decade of persecution after another. He called this idea the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history.” Without denying that suffering has been a part of Jewish history, we can be grateful for the moments of “repeated joy” that have been part of our history and the resilience that has brought us through the suffering. Additionally, by having a more global understanding of Jewish history, we know that this lachrymose view is also largely an Ashkenazi version of Jewish history. We can easily look to centuries of Jews living in Muslim Spain or at how Jews thrived in North Africa and the Middle East. Jewish history is infinitely more complex and varied than the stories of constant persecution. Halleluyah offers us a way into Jewish history, as it does with the story of the Exodus, to be grateful for our survival and for our flourishing. This does not negate the suffering nor does it prevent us from learning from or being motivated by it.

As humans, our brains naturally engage in something called “negativity bias,” meaning that we tend to think about bad things more than we think about good things. From an evolutionary perspective, this was advantageous by keeping us safe by thinking frequently about things like predators. Today, this is largely unnecessary and distorts our view of reality. Dr. Rick Hanson describes our brains as “Velcro for the bad and Teflon for the good. We have to learn to weave the positive into the fabric of our brains.” Jewish tradition is overflowing with ways to do this work and actually invites us to say 100 blessings a day (Menahot 42b). Our days are to be filled with gratitude.

In the world of community organizing, one of the standard questions that people ask to determine what issues people are passionate about is: “What keeps you up at night?” This question mirrors the tikkun olam framework that focuses on the brokenness. One organizer taught me to ask the question: “What gets you up in the morning?” This question focuses on hope, joy and gratitude as the path to political work. Particularly in Jewish tradition when the first words out of our mouth are Modah/Modeh ani/“I give thanks.” Gratitude is what gets us out of bed in the morning and into the world. By deepening our feelings of gratitude, we can deepen our expressions of gratitude. The depth of her gratitude motivated Donna Schneiderman to take action. Her gratitude was deep enough for it to be politicized and actionable in the world. When we pause to say a brakha over food, that can move us to take action against hunger and poverty. When we light Shabbat candles, that can move us to ensure that all working people have time off. When we bensch gomel after surviving a surgery or illness, that can motivate us to ensure that all people have access to health care. Our gratitude—while individual and personal—is interconnected to other individuals and systems that make our lives possible. Halleluyah can be a way to acknowledge our own suffering, but not be limited by it. Halleluyah offers a way to connect with integrity to the broad systems that shape our lives. Halleluyah is about honestly living into our joy, even while suffering is all around and within us.

This suffering will always be a part of our justice work. As long as there is justice work to be done, there will be pain and brokenness. As a people, we have a choice about how to approach this pain. We can let the broken shards be our focus or we can let the knowledge of past repairs, both mythic and historical, inspire us to make the world a more whole place. It may appear naive to focus on the good in working for justice. My hope is that by focusing more on gratitude, we will be able to tend to both our own suffering and the suffering of others with more spaciousness, more compassion and with more clarity—and that would warrant a halleluyah.

Rabbi Alex Weissman (RRC ’17) serves as the Rabbi at Congregation Agudas Achim in Attleboro, MA and as the Rabbinic Organizer at T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. Previously, Alex served as the senior Jewish educator at Brown RISD Hillel, where he taught Torah and Jewish practice, and fostered creative approaches to Jewish life. While a student at RRC, Alex served as a rabbinic intern with Avodah, piloting a new model of Jewish and spiritual support for young activists. He worked with JOIN for Justice as their Philadelphia Area Coordinator, exploring new opportunities for JOIN. He was also a Social Justice Rabbinic Intern with Congregation Rodeph Shalom and POWER, supporting their multifaith congregation based community organizing, and was a summer fellow with T’ruah. Alex also served two synagogues, Congregation Beit Simchat Torah and Temple Shalom of Newton, as a rabbinical intern.

Prior to attending rabbinical school, Alex worked at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah as their first Social Justice Coordinator, moving forward campaigns to support LGBTQ homeless youth and LGBTQ eldercare, in addition to creating learning and training opportunities for Jewish clergy to deepen their skills in serving LGBTQ communities. He was in the inaugural cohort of the Grace Paley Organizing Fellowship with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, during which he served as chair of the Sh’lom Bayit: Justice for Domestic Workers campaign and later served as a member of the board of directors.

Prior to his work as a community organizer, Alex worked in LGBTQ public health at Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project, Fenway Community Health, and the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training. Alex lives in Providence, R.I., with his partner, Adam, the source of much Alex’s gratitude.